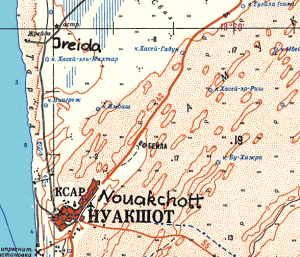

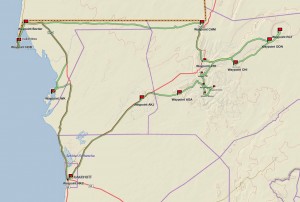

In preparation for a longer upcoming trans-Saharan journey we conducted a scouting trip in Mauritania during January 2015. We spent roughly two weeks traversing 1,400 miles, mostly off-road, in a loop from the capital Nouakchott north along the coast to the border crossing near Nouadhibou then east to Choum and southeast via Chinguetti and Ouadane into the Eye of the Sahara (Geulb er Richat) and back around south west to Maaden through the White Valley to Azoueiga then Akjout and back to Nouakchott. The primary goal of this mission was to assess terrain, driving conditions, logistical concerns and approximate timeframes for a future expedition.

< MAURITANIA REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO IWIK >

The journey begins in Nouakchott, the capital of Mauritania, and the nation’s largest city. The name means “place of the winds” and blowing sand often seems to give the blue sky a slightly beige tint. It is a strange capital, without a distinctive architectural style or visual unity. That lack is easier to understand once we realize that it was just a small village until 1960, when it became the capital of the newly independent nation. Nouakchott was chosen because it was physically in the middle of the country, and so represented a kind of symbolic unity for the young state. Starting out as a sleepy administrative capital, it quickly grew larger than planned. The population exploded during the 1970s when Mauritania was hit with severe droughts devastating the rural countryside where farmers and nomadic herders depended on small agricultural holdings and livestock to survive. Desperate families flooded into the capital expanding the perimeter of the urban center out along the edges. Over time the newcomers were absorbed into the fabric of a growing city.

As we drive along the tar road heading north, it is hard to tell where the city limits end. Nomadic families have set up tents and more permanent structures in a semi-inhabited sprawl that spreads into the desert. People continue to gravitate here, some out of need, others out of ambition. Under its dusty desert veneer, Nouakchott is a vibrant hub of activity, and a place where all levels of society intersect. Rich walled compounds are within a few blocks of poor cement block single room houses. Camel herders bring their animals to the edge of town to sell fresh camel milk to urban residents. The centers of government and culture connect with the masses here. And there is just a little bit of chaos in the streets, where despite traffic signals and roundabouts, drivers don’t always mind the rules and sometimes turn the wrong way into a traffic circle to make a quick left. The impression is of an energetic capital, on the verge of economic expansion, where people are working hard to get ahead as they can.

Nouakchott’s flat spread out structure means the city doesn’t really have a definitive skyline, though there are a few prominent landmarks, notably the Mosquée Saudique, and a number of tall buildings under construction, possibly hotels or office spaces. From the bustling central market area it is hard to realize that we are only five kilometers from the Atlantic ocean. Nouakchott is simultaneously a desert and a coastal town.

The Porte de Peche is the most notable touristic attraction in the city, though it is not for tourists and it is hardly an “attraction.” It is a very busy working fishing port with an almost byzantine functional structure, that at first glance seems like total anarchy, but upon further inspection reveals a well-choreographed system to get the fish from the boats to market quickly. For an outsider it is hard to understand what is going on, but apart from us, each person on the shore has a role and knows what to do. As a ship comes in, porters run out into the water to meet it, and begin the process of unloading trays and buckets of fish. Further up the beach crews stand ready to sort and process the fish, some of which will be sold at the market right there, and some of which will be dried for sale further away.

The brightly painted pirogues used by the fishermen are sturdy wooden boats, about 40 feet long, and capable of withstanding an unrelenting surf that can be quite dangerous. Though today the Atlantic seems calm, we hear that it can often be treacherous and men sometimes go out to sea and never return. Despite the risks, small crews of mostly Wolof and Fula men go out daily to harvest the riches of Mauritania’s coastal waters. According to the BBC many of the Mauritanian fishermen are originally from Senegal or the Gambia, where the tradition of fearless fishermen is well entrenched. Sometimes the men spend the night out at sea, as that is when fish rise to the surface to feed. The work day for the fishermen is long and hard. The pirogues start to return in the early afternoon, but the peak time to see them is around 5pm.

As far as the eye can see, the colorful pirogues float with nets cast, while on shore porters and traders wait patiently for their return. But beyond our line of vision, Mauritania’s waters are even more crowded. Commercial fishing vessels from Europe, China, Belize, Korea and Russia, and even some unidentifiable “pirate” fishing boats follow the continental ledge in search of sardines, sardinella, and mackerel. These large commercial trawlers can catch, process and freeze 250 tons of fish a day.

Since the 1990s, Mauritanian waters have experienced a rapid decline of fish stocks. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, as cited in The Guardian, west African fishing grounds are over-exploited to the detriment of more than 1.5 million local fishermen. The local fishermen are forced to travel further and compete with the commercial ships in dangerous waters unsuitable for their small wooden boats.

The issue is a complicated one, as licenses granted to foreign fishing companies are an important source of income for this desert state at the same time that the local fishing industry is responsible for the livelihood of a significant portion of the population in certain regions. Fishing accounts for 10% of GDP and between 35% and 50% of Mauritanian exports. It also provides 29% of the income for the national budget and generates 45,000 direct and indirect jobs, accounting for 36% of all employment, according to an EU study. It is estimated that 31% of these jobs are generated by small-scale fishing, and 12% by industrial fishing.

The Mauritanian government with support from various other nations and development projects has tried to establish a more effective fisheries management system to protect this important resource, though enforcement has proved challenging.

Here on the shore, there is not much discussion of policy as people are too busy making a living from the sea. The boats are full of fish, and lines of porters work swiftly to unload them in perfect rhythm. No one seems to direct anything, but everyone does their job seamlessly. Independent traders rush up to the side of the pirgoues even before the porters are done, competing with each other to buy the other species of fish that were mixed in with the primary catch. They will take them to the market, where the fish are sold sometimes whole, or sometimes by the slice. The mass of people on the beach and in the adjacent market are all dependent on the water’s wealth.

Ironically, despite the great wealth of their seas, the average Mauritanian culturally identifies with the desert heritage, so outside of the coastal area, fish is not a staple food. In fact, according to the EU study, the consumption of fishery products in Mauritania is very limited and has not increased despite the fall in livestock production caused by drought. The study cites the lack of a tradition of consuming fish, limited purchasing power and failure by households to adapt to preserving and preparing fish as the main reasons. Apart from what is consumed in Nouakchott, much of the fish dried or smoked here goes to market in Senegal or Mali.

WHERE WE ARE

The Islamic Republic of Mauritania is the eleventh largest country in Africa. Although the country is mostly desert (90% of the land is within the Sahara), it has 468 miles of Atlantic coastline. It is roughly three times the size of New Mexico. Most of the population is concentrated in the coastal cities of Nouakchott and Nouadhibou and along the Senegal river in the southern part of the country. The nation shares borders with Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, Algeria, Mali, and Senegal. The official language is Arabic, though the regional dialect is Hassaniya, and many people also speak French (Mauritania gained independence from France in 1960).

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

NOUAKCHOTT / IWIK – 170 miles – Estimated drive time 4 hours

(click map for larger view of route)

Starting from the capital city of Nouakchott, we top off supplies before leaving in the morning. The day’s drive of roughly 170 miles should not be difficult, as it begins on the tar road headed north before turning west across the sandy desert pistes. The desert terrain here is easy, with flat sandy open desert most of the way. The pistes are well-defined approaching Iwik where we will camp for the night on the coast.

TERRAIN DETAIL: NOUAKCHOTT

The city and its near environs are mostly flat and sandy, with the desert going right up to the Atlantic coast. The coastline includes shifting sandbanks and sandy beaches and there are areas of quicksand close to the harbour.

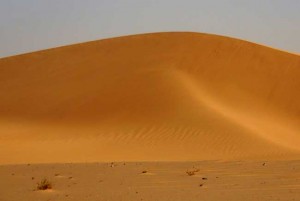

MIGRATING SAND DUNES

Nouakchott is endangered of being covered by sand dunes advancing from its eastern side which pose a daily problem. The wind-driven sand grains that we can see blowing across the desert, or cascading down the leeward side of the dunes, are actually the visual manifestation of how dunes grow and slowly migrate. Though beautiful to watch this is a grave concern in places where the relentless advance of desert dunes is a serious threat to habitation and agriculture. In some places dunes advance at a rate of 20 meters per year according to NASA researchers studying the issue.

CURRENT WEATHER

Detailed weather: Nouakchott

THE SAHARA IN MAURITANIA

Terrain: In the western portion of the Saharan Zone, extending toward Nouakchott, rows of sand dunes are aligned from northeast to southwest in ridges from two to twenty kilometers wide. Between these ridges are depressions filled with limestone and clayey sand capable of supporting vegetation after a rain. Dunes in the far north shift with the wind more than those in the south. The regions of Tiris Zemmour, Adrar and Hodh ech Chargui are vast empty stretches of dunes alternating with granite outcroppings. After a rain, or in the presence of a well, these outcroppings may support vegetation. The plateaus of Adrar and Tagant, where springs and wells provide water for pasturage and some agriculture, can be lush.

Weather: Temperature fluctuation during the day can be extreme. In December and January, temperatures go from morning lows of 32°F/0°C to afternoon highs of 100°F/38°C. In the hottest summer months highs typically reach 120°F/49°C. Throughout the year, the harmattan (a dry, dusty easterly or northeasterly wind on the West African coast) often causes blinding sandstorms. Rain typically falls during the “hivernage” (July to September) when isolated storms drop large amounts of water in short periods of time. However, a year, or even several years, may pass without any rain in some locations.

Vegetation: In mountainous areas with a water source there are small-leafed and spiny plants and scrub grasses suitable for camels. Dunes sprout sparse vegetation after a rain (the seeds of desert plants can remain dormant for many years). In depressions between dunes, where the water is nearer the surface, some flora–including acacias, soapberry trees, capers, and swallowwort–may be found. Saline areas have a different kind of vegetation, mainly chenopods, which are adapted to high salt concentrations in the soil. Cultivation is limited to oases, where date palms are used to shade other crops from the sun.

THE COMPLETE ROUTE

(click map for larger view of route)

Waypoint: Nouakchott

Drive: Nouakchott to Iwik

Waypoint: Iwik

Drive: Iwik to Nouadhibou

Waypoint: the Border

Waypoint: Nouadhibou

Waypoint: Cap Blanc

Drive: Nouadhibou to Choum

Waypoint: desert piste

Waypoint: Ben Amara

Waypoint: Choum

Drive: Choum to Ouadane

Waypoint: Atar

Waypoint: Ouadane

Drive: Ouadane to Richat

Waypoint: Richat

Drive: Richat to Chinguetti

Waypoint: dunes

Waypoint: Chinguetti

Drive: Chinguetti to Tergit

Waypoint: Tergit

Drive: Tergit to Maaden

Waypoint: desert oases

Drive: Maaden to Azoueiga

Waypoint: White Valley

Waypoint: Azoueiga

Drive: Azoueiga to Nouakchott

Waypoint: Akjout

Waypoint: Nouakchott

ABOUT THE TRUCK

Our journey was made in a locally-sourced diesel powered 2010 Toyota HiLux with Dunlop Sand Grip tires. The HiLux is one of the most common trucks seen on the pistes in Mauritania and is relied on by drivers here. Though not available in the U.S. market, over 13 million Toyota Hilux have blazed trails around the world since 1968. From the Arctic to the Sahara, this unstoppable pick up has earned trust and admiration for its off-road capabilities and endurance.

NOMADS AND URBANIZATION

Mauritania’s population underwent dramatic change as a consequence of the droughts of the 1970s, moving away from their traditional lifestyles as pastoral nomads or sedentary agriculturists. According to the U.S. Library of Congress Country Study, 90 percent of the population were living traditional lifestyles dispersed across the countryside in the 1960s. The percentage of the population that was still nomadic or seminomadic dropped to less than 25 percent by the mid-1980s. While many factors contributed to this shift, including long-term efforts by colonial and independent governments to settle the nomads and new employment opportunities associated with mining and export industries, the droughts and resultant desertification of the land were paramount. Counting both resident and temporary urban dwellers, some sources in the late 1980s placed Mauritania’s urban population at or above 80 percent.

NOTE: This is the first in a series of segments highlighting details of our Mauritanian scouting misson. Each segment will focus on a specific location or region. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in January 2015 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads supported by a local Mauritanian crew. For more information about the team or the specifics contact us.