A solo trip into one of the most remote places in the continental U.S., the Maze district of Canyonlands national park, offered some interesting challenges and an amazing experience in the solitude and splendor of the wilder desert landscapes. The route chosen for the six day 450-mile journey was almost completely off pavement (and off grid) apart from the initial and final sections of the loop that started and ended at Moab, UT. The primary goal of the trip was to get an overall introduction to the Maze district and work on preparing for logistical contingencies in remote environments.

< GALLERY: INTO THE MAZE | THE MAZE REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO NORTH POINT >

The familiar red rock landscape of Moab had already morphed into a dry sandy desert before I turned off pavement and onto the dirt just south of I-70 near Green River. I was headed into the unknown (for me), on a journey about exploration and discovery in strange but beautiful landscapes kept wild by their inaccessibility. I had chosen to make a solo trip into The Maze, the most remote part of the Canyonlands national park, to challenge my skills and work out a number of different scenarios related to the contingencies of a remote expedition, unsupported and off-the-grid. And I selected a route via the San Rafael desert that would present a few navigational challenges amidst criss crossing trails in harsh desolate terrain.

The San Rafael desert includes about 2,000 square miles of public land administered by the BLM, centered on a geological feature known as the San Rafael Swell. The Swell consists of a giant dome-shaped anticline of sandstone, shale, and limestone that was formed some 60-40 million years ago. I-70 goes right through the center of it, dividing the desert north and south, and the area is full of scenic sandstone formations, deep canyons, desert streams, and expansive panoramas. My route only crosses the very smallest southeastern corner of it, but passes through several different types of terrain.

As I moved south on a nicely graded dirt road and away from “civilization” I felt a heightened sense of situational awareness seasoned with a touch of excitement. Everything was “new.” There was also an element of nervous concern. Recent heavy rains may have washed out sections of the “road” and I might have to turn back at some point. But for now it seemed the long drive southward would continue on straight and flat with no navigational issues in this first section, as there was only this one dirt road. The terrain was typical desert, with bare sandy earth, punctuated by sparse green plants and dry hills. Just as I began thinking to myself that the drive down might get a bit boring, the trail dipped to reveal strange shaped hills in the distance. At first I thought it was some kind of construction site, then as I got closer I could see that it didn’t seem to be an excavation or a man-made dirt pile, but was some kind of naturally occurring form.

I stopped briefly to explore this otherwordly landscape. At the base of these hills the outcroppings were some kind of white stuff. The texture kind of looked like cement (to my urban eyes) or perhaps some kind of coarse salt. It was hard to tell if it had been “piled up” or just happened to be there.

According to the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, the area of the San Rafael Swell is a microcosm of the entire Colorado Plateau, with a concentric series of rock formations from different geological eras, shaped by uplift and erosion. Its stark and dramatic scenery stems from spectacularly exposed sedimentary strata. Each rock formation has created its own unique world. I am just seeing a tiny sample of it here. Far beyond this little corner of the desert, there is much more to explore. Colorful Entrada Sandstone forms the brilliant orange cliffs and towers of Cathedral Valley, Salt Wash and the hoodoos of Goblin Valley. There are psychedelic badlands of the Morrison Formation, an intricate “painted desert” and dark volcanic mountains. But the magical landscapes would have to wait for another time, if I wanted to get to The Maze.

I continued moving southward following the trail as it passed through colorful hills that reminded me of the “Painted Desert,” and the terrain began to get a little wilder looking. Approaching an area on the map called Horse Bench Reservoir, I could see water shimmering in the distance. It was not a mirage. There was suddenly a vast lake in the middle of the desert. It was breathtaking. The painted hills reflected in the mud colored water while rock pillars protruded like cypress stumps in a swamp, as if this was some weird parallel universe.

I was lucky, because while the recent monsoon rains had pushed the water level up and clearly flooded some areas that were not usually underwater, the road remained passable for the Jeep. I continued my journey south, and the navigation got a little more complicated as intersecting roads and turnoffs started connecting with my trail. Still, the “main” road was pretty obvious, and I drove on into some more rugged desert for a stretch before reaching the San Rafael River. If I’d had more time to explore, there is a nice hike in a non-technical slot canyon at Moonshine Wash a bit further south. I’ve been told the hike is relatively easy, with spectacular scenery, interesting history, and some cool artifacts. Apparently the area was popular with bootleggers during prohibition and it is possible to see the remnants of old stills around there. I put that on my “to do” list for next time.

My route turned to the east and then again southeast, and along the way in the middle of what seemed like “nowhere” there was a grave marker. I later learned that it was for a 64-year-old road worker, Charles Watterson, who was shot at this spot (referred to in the news article as “Robbers Roost”) by a man who was hiding behind some rocks (and did apparently steal some money from the deadman, making the place name factual). This happened in 1998.

On the map it seems that the actual “Robbers Roost” area is further south, but I imagine that it was never quite specifically delineated. Sandwiched between the Colorado River, Green River, and Dirty Devil River, the inhospitable terrain crisscrossed with steep-walled canyons and hidden ravines received its colorful name in the 1870s when an outlaw named Cap Brown ran stolen horses through the area. But the area’s most renowned “resident” was Butch Cassidy, who began to use the Roost in the 1880s. Robbers Roost afforded hundreds of hiding spots, was difficult to penetrate, and became one of several hideouts along the “Outlaw Trail.” Despite some sporadic attempts, the authorities never successfully penetrated the refuge. It gained a reputation as being impregnable, and stories about its defenses contributed to its legend. According to Utah Adventure Journal, the last 45 miles of trail into the Roost required a thorough knowledge of the terrain because water for horses could only be found in one place. The Roost was largely abandoned as an outlaw hangout after 1902 when Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid departed for South America.

My route continued due south once I crossed the San Rafael River (where there is a paved bridge), and I could see the La Sals to my east. The mountains were like a welcome beacon shining across the desert constantly reassuring me I would not get lost–as long as I could see them I would always be correctly oriented without reference to a compass or a GPS. From this vantage point I could see several distinct terrain types between myself and the mountains. I was nearing my “destination” for the day, a spot I had chosen just north of Horseshoe canyon that seemed like it would present some scenic camping possibilities. The terrain was changing a bit too, with more of the familiar red rock popping up here and there. I turned east off the main trail a little beyond Lookout Point, heading for Keg Knoll. Though the terrain looked flat at first, I soon saw something seeming to rise up out of the flatness on the trail ahead.

As I approached it, the terrain began to change character again, showing its rougher more desert-like side. The “knoll” itself was a rocky outcropping, and the wind was blowing harshly across its face. It didn’t seem like the heights would be a good place to camp at all. It was exposed and open, and the wind was picking up. I drove a little further along, until I came to a spot where I saw tracks pulling off to the side, and followed them down into a more protected “bowl”-like area on the other side of the “knoll.” The terrain itself was smooth flat rock and the view was beautiful. There were a few old fire rings scattered around and I decided to make camp somewhere nearby, though the wind was getting worse.

I had chosen Keg Knoll as my camp spot without ever having seen the area, based on research, maps and other people’s trip reports. I had wanted a camp location close enough to the park entrance so that I would not have a long drive tomorrow, but I wanted to be on BLM land where wood fires were permitted, and in a general area that would bring me through some navigational challenges. I also wanted to be somewhere beautiful and interesting for this first night out under the stars. From what I could learn prior to the trip, Keg Knoll fit those requirements. One of the big challenges of this trip had been planning the route through such a remote area in an unfamiliar part of the country. While the actual segment within The Maze was relatively straight forward to plan with all the information about distances and campsites available on the Canyonlands national park website (supported by a system for obtaining permits that reserved exact sites and dates), planning for the segments outside the park was more complex.

I created my route referencing different maps and anecdotal research online, picking out potential campsites ahead of time so that I would have some kind of “endpoint” at a reasonable day’s driving distance. Of course, I could always change my mind if I saw a great spot somewhere else, but in the worst case scenario I wouldn’t find myself searching for a place to camp as the sun was setting in terrain that was not ideal. I also prepared optional routes for some segments of the journey, so I would have a “plan B” ready to go in the case that my original choice of route proved impassible or impractical. This was an important safety factor for a trip with fuel management considerations and a tight time frame.

With the wind blowing harder, I took a walk around to try to find a protected spot to put my tent on the east side of the Knoll between the heights and a small ridge. There were lots of little “bowls” full of plant life, with sweeping flat stone around them. It was another otherworldly landscape and I was enjoying the impromptu hike after a long day in the Jeep. From what I had learned, there are some great hikes to be done right near here, with some unusual features including something called “the dragon’s teeth” near Colonnade arch. I wouldn’t have time for that this trip, but am adding it to my list for next time. Just wandering around exploring the terrain near camp had taken me much further than I expected and reminded me that distances in the desert can be deceptive, especially when I keep getting distracted by interesting details that have me zig-zagging in random directions. Turning back towards the Jeep, I was glad it was bright red and easy to spot in the desert. The sun was getting lower in the sky and I didn’t have that much time to get settled in.

Deciding on a spot that was a bit hidden and protected, I pulled the Jeep in to block the wind as best I could and quickly set up my tent, weighing it down with my extra water bottles and bundles of firewood. Another complication for a trip so far from “homebase” related to the limits it imposed on my equipment options. Because I had to fly into Utah initially, I had to pack everything in luggage that met the airline’s size and weight requirements. I was limited to one bag, not to exceed 62″ (157.48 cm) in overall dimensions (length width height) or 50 pounds (22.68 kg), so taking my favorite tent was not an option. I needed something much lighter and more compact but with more room than an ultralight backpacking tent. My compromise choice was to purchase a cheap tent that weighs under five pounds but is large enough to spread out and take shelter in. Though far from the “ideal,” this “disposable” tent has held up to the rigors of some fairly rugged camping in high winds before, and would perform well during this trip too. The last rays of the sun were turning the landscape to gold as I finished setting up camp and sat down to take in the magnificent sunset.

With the sun gone, the temperature dropped quickly. It was late October, when the “average” temperature ranges (in degrees Fahrenheit) from highs between 74-56 during the day to lows of 42-30 at night. The cold and the wind made for uncomfortable camping partners, and I added some layers and my winter hat. The wind was gusting hard now, and it took a bit of doing to get my fire going. Hidden from the “road” below the edge of the knoll I was invisible here, and my thoughts strayed to the outlaws of old as I settled in to watch the night fall. The wind finally began to die down. Clouds were moving in so I didn’t see many stars, but the full moon rose up over the ridge, shedding an eerie light on my campsite. The desert around me was quiet apart from the crackling fire flickering warm and cozy, making for a calm and beautiful first night…

> CONTINUE: DAY TWO — KEG KNOLL TO NORTH POINT

< GALLERY: INTO THE MAZE | THE MAZE REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO NORTH POINT >

WHERE WE ARE

The Maze is one of three distinct districts of the Canyonlands national park, located near Moab, Utah. This journey loops north of the town of Moab, then west to Green River and south into the San Rafael desert to reach the Maze district of the park, continuing south into the Glen Canyon Recreation area and then east to Blanding and back north to close the loop.

THE COMPLETE JOURNEY

The Maze Report Home

Gallery: Into the Maze

Day One: Moab to Keg Knoll

Day Two: Keg Knoll to North Point

Day Three: North Point to Golden Staircase

Day Four: Golden Staircase to Maze Overlook

Day Five: Maze Overlook to Hite Crossing

Day Six: Hite Crossing to Moab

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

MOAB / GREEN RIVER / KEG KNOLL – 101 miles – Estimated drive time 5 hours

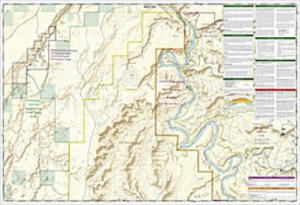

(click map for larger view of route)

Starting from Moab with a full tank of gas and two five gallon gas cans additional, I head north on Highway 191 to Crescent Junction, then take I-70 West to Green River. I top off gas again at Green River, then say goodbye to civilization as I move on to dirt, heading south through the San Rafael desert to a spot called Keg Knoll, not far from Horseshoe Canyon. The road is maintained and until the turnoff for Keg Knoll, is quite a major artery, so the driving is easy and smooth through varied desert terrain.

ABOUT THE SAN RAFAEL DESERT

Much of the area around the San Rafael Swell is remote and aside from Interstate (1-70), is mostly undeveloped with only old uranium mines, dirt roads and some simple recreation facilities. The BLM advises visitors to bring maps, as many roads are not signed. Motorized vehicle usage is limited or prohibited in certain areas (see the Emergency Road Closures for current information). Additionally, the BLM reminds those traveling in the desert of some basic safety precautions: Never camp or park your vehicle in a wash or stream bed and avoid hiking in narrow canyons when rain is a possibility. A dry wash can flash flood in a matter of minutes even if you don’t see a cloud in the sky. Many roads within the Swell cross soil types that are extremely muddy after storms and during periods when snow is melting. At such times, these roads become virtually impassable. Obtain a long-range weather forecast before traveling into the area. There are very few sources of potable water in the San Rafael Swell, so make sure to carry at least one gallon of water per person per day. Exercise extreme caution when exploring around old mines. Besides the danger of being caught in a collapsing tunnel or falling into a hidden shaft, heavy concentrations of radioactive radon gas are known to accumulate at the entrances to old uranium mines in this area. Note that no permits are required for individuals and small groups for non-commercial use. For more information contact the Bureau of Land Management’s Price Field Office at 435-636-3600.

ABOUT THE JEEP

This journey was made in a 2015 4-door Jeep Wrangler Rubicon sourced from Barlow Adventures in Moab, UT. Traveling alone in such a remote area made vehicle capability and reliability top priority. Barlow’s Jeeps are professionally modified specifically for Moab’s adventurous trails and back roads, with 3″ suspension lifts, 33″ heavy-duty off road tires and extra undercarriage armor. The company has an outstanding reputation within the off-road community for the quality and condition of its Jeeps as well as for the general support provided. The specific Jeep used for this trip was a Hard Rock edition with about 6,000 miles on it equipped with BF Goodrich KO2 tires and in top condition. There would be no worry about mechanical breakdown and the Jeep was more than capable of facing any of the terrain challenges expected on this route.

SPOTLIGHT: THE CHALLENGE OF PLANNING

Just getting here had presented some challenges of its own. For someone coming from outside the local area the trip requires careful advance planning and preparation. In addition to obtaining the necessary permits to camp in the Maze district, thought must be given to routing in and out, fuel management, safety precautions, weather and equipment. The area’s remoteness requires a level of self-sufficiency and the ability to “self-recover” should a vehicle breakdown or get stuck. The National Park Service reminds visitors that a high-clearance, low range, four-wheel-drive vehicle is required for all Maze backcountry roads and discourages inexperienced drivers from attempting these routes. Additionally, they suggest that all drivers carry at least one full-size spare tire, extra gas. extra water, a shovel and a hi-lift jack.

SUGGESTED MAPS

USGS 1:100,000 topographical maps were used for general routing and orientation, as they provided the best overview of the journey and include the prominent distant terrain features that define the landscape. The journey spans five sector maps (links download full resolution maps from USGS store):

Moab – 1:100,000 topographical map

San Rafael Desert = 1:100,000 topographical map

Hanksville – 1:100,000 topographical map

Hitecrossing – 1:100,000 topographical map

La Sal – 1:100,000 topographical map

For more detail, National Geographic Trails Illustrated maps were used. These printed maps come on reinforced water-proof and tear-resistant material, and include detailed information on recreational trails and points of interest. There are several maps that cover areas included in this journey, though the most critical are the Maze and Canyonlands maps. An important note: be aware that the Maze district map DOES NOT show the Hans Flats Ranger station or the exit to Hite Crossing.

Canyonlands National Park – (210) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 Topographic Map

Maze District: Canyonlands National Park – (312) Trails Illustrated 1:35,000 Topographic Map

Moab North – (500) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 & 1:35,000 Topographic Map

Moab South – (501) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 & 1:35,000 Topographic Map

San Rafael Swell – (712) Trails Illustrated 1:90,000 Topographic Map

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area – (213) Trails Illustrated 1:90,000 Topographic Map

CURRENT MOAB WEATHER

GEOLOGY OF THE SAN RAFAEL SWELL

The story of the San Rafael Swell’s unique geology begins roughly 250 million years ago in the Permian period, when it was a seashore. Layers of sandstone were deposited as beach dunes piled up, forming Coconino Sandstone, a rough irregular stone with cross-hatching and variable hardness that forms small fins and ledges as it erodes. The Coconino was covered by a layer of limestone when the ocean overtook the shore. This Kaibab Limestone is a thin layer very resistant to erosion that forms the base of many of the flat open areas in the upper San Rafael.

As the ocean moved back and forth over the area, more layers of soft mud, mudstone, and sandstone were deposited. Then, in the late Triassic Period (roughly 200 million years ago), western Utah rose up out of the ocean, high above sea level, while the eastern side remained flat. The breakpoint was along a weak spot in the crust known as the “Wasatch Line.” During this transition a variable layer of sandstone and mudstone formed, called the Chinle Formation (the Chinle Formation is the site of uranium and radium deposits). As eastern Utah dried out it formed a desert of shifting sand dunes. First came the Wingate Sandstone, which forms towering cliffs, followed by Kayenta Sandstone, which created erosion-resistant layers protecting the Wingate cliffs below it, and finally, at the start of the Jurassic Period desert dunes formed Navajo Sandstone. But the dunes soon gave way to a wet floodplain, as a narrow finger of ocean intruded north-to-south creating the Carmel Formation along the border between the western highlands and the eastern plain. Interestingly, many of the later Jurassic period rock layers that are familiar in the Moab area, are NOT found in the eastern San Rafael.Geologists theorize that a pool of upwelling magma that didn’t quite make it to the surface pushed the rock layers of the San Rafael upwards like a giant blister. The steep eastern slope of the uplifted area is exposed on the east flank of the San Rafael Swell, and is called the San Rafael Reef. This upsloping Navajo Sandstone forms an impressive shark-tooth line of steep sandstone. The western slope of the Swell is more gradual, eroding into canyons, spires, and castles. When the Great Basin fell and stretched away from the Colorado Plateau (this plateau includes the San Rafael and Moab areas) during the Tertiary period about 65 million years ago, erosion began to wash the rock layers away. Once the Cretaceous Period deposits were eroded, the original uplifted region broke the surface again. As the “blister” broke, the reef edge was exposed. Some highlands were protected by hard underlying rock layers, forming large flat areas. Deep gorges were cut through the harder rock as water drained from the uplifted areas. Where a small bit of hard rock was spared in a higher layer, castles and spires were left standing across a dynamic and varied landscape of open vistas, cliffs and deep gorges that define the San Rafael today. (For more details see the full explanation by UtahMountainBiking.com)

HISTORY: URANIUM AND THE COLD WAR

According the the BLM Price Field Office, the recent history of the San Rafael Swell is sprinkled with anecdotes and artefacts of the Cold War — notably the quest for weapons grade uranium. Native Americans were the first to mine the ore, using it to create colored pastes that were applied as war paint. Small-scale mining efforts in the 1870s and 1890s also focused on producing uranium as a dye colorant in manufacturing and for photographic or medical experimentation. Serious commercial uranium exploration and mining started in 1898 at Temple Mountain when the ore was discovered there by Joe Swasey and folklore says that Madam Curie later visited the mines with Swasey as her guide. The north side of Temple Mountain would continue to be mined for many years, however, the importance of this heavy metallic element was significantly and permanently changed with the development of nuclear weapons for military applications during World War II. In late 1947 military personal suddenly appeared in the Buckhorn Flat Area, provoking widespread speculation and rumors that were further fed by the atmosphere of Cold War secrecy. Eventually it was announced that explosives were to be detonated deep underground to test the structure of the rock. Uranium exploration and mining intensified after the war and Utah became a major contributor to uranium production in the United States. Remnants of some of these mines remain visible around the San Rafael desert today, but perhaps more interesting are the rags-to-riches-and-back chronicles of the men who staked the claims and dug the “tunnels of hope and heartbreak.” At the height of the Cold War uranium boom during the 1950s, Emery County was the second largest producer of uranium in the United States. More than fifty thousand claims were filed in the County Recorder’s office between 1950 and 1956. Many men explored for uranium in the Swell trying to make it rich, but very few did. In most cases prospecting for commercial minerals was a fruitless endeavor. According to Owen McClenahan, an active prospector within the area, “One of the worst things that could happen to a prospector would be to find just enough to raise his hope, his dreams, and encourage his irresponsibility to raise money in any devious way he could. Many men lost everything they owned, including their wife and family.” And even for those who were successful in the search for uranium, the story ended once rich deposits of the ore was discovered in the Belgian Congo. By the mid-1960s the boom-cycle was over as the market collapsed in response to the end of government purchasing and the increasing availability of cheaper foreign sources. (Adapted from “Four Swell Stories” by BLM-Price Field Office. For an in-depth oral history on San Rafael uranium mining, see this report)

NOTE: This is the first in a series of segments highlighting details of a solo Jeep trip into The Maze district of Canyonlands national park, in Moab, UT. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in October 2015 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads. For more information about the specifics contact us.