A solo trip into one of the most remote places in the continental U.S., the Maze district of Canyonlands national park, offered some interesting challenges and an amazing experience in the solitude and splendor of the wilder desert landscapes. The route chosen for the six day 450-mile journey was almost completely off pavement (and off grid) apart from the initial and final sections of the loop that started and ended at Moab, UT. The primary goal of the trip was to get an overall introduction to the Maze district and work on preparing for logistical contingencies in remote environments.

< BACK: TO GOLDEN STAIRCASE | THE MAZE REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO MOAB >

First light washed over the Maze imbuing the landscape with a purple hue that lasted a few fleeting moments. The silence of morning was almost loud as the rocks began to glow. My campsite was tucked into a fold of the ledge and invisible to the world. Not that there was anyone around to see. I was beginning the fifth day of self-imposed solitude deep in the mystical heart of the canyons. I wanted to linger, but I had to get a head start on the drive day, which was going to be a long one. I had about sixty miles of driving ahead of me, and though the last few would be back on pavement, there was still quite a bit of dirt to cover.

After packing up camp, I couldn’t resist taking one final short walk along the rim of the overlook, stopping to just sit on a rock and gaze down into the chasm. I was feeling at one with the landscape. Over these past few days I have learned to see differently. I have gotten beyond “looking” at the land as “scenery,” to the point where I am interacting with it up close and personal, exploring deep inside it’s folds of rock, feeling its texture, becoming comfortable in its extremes. I have almost become a part of nature, finding my place with the birds and the small rabbit that is looking for food in the brush not far from my tent. There was something magical about this “transformation” that allowed me to see what I couldn’t see before. I could only imagine the experience of the true “explorers” who first mapped this area.

The canyonlands had remained “terra incognita” for a long time. According to The Administrative History of Canyonlands National Park, the remoteness and hostility of the terrain kept this place “wild” — even in ancient times the region was something of a hinterland outpost, a place of refuge and repository of myth for the Anasazi and other pre-modern cultures. Considered “badlands,” it was avoided by Spanish and Mexican traders and only a few trappers, outlaws, Ute and Navajo knew the area. Though various exploratory expeditions had poked around the region, most never considered the land valuable or “worthy” of the effort to do more until John Wesley Powell‘s famous 1869 river trip. While most of their predecessors had been motivated by economic and religious interests, the historical “great explorers” like Powell, set out to map the “unknown” and cross frontiers in epic (and sometimes tragic) journeys across the harshest landscapes of the west. Powell’s account of his river expedition created a modern legend, a dramatic tale set in an almost mythic landscape that inspired generations, defining the region’s identity in the public imagination for the next hundred years — until Ed Abbey updated it with the 1968 version in “Desert Solitaire.”

My own journey was feeling pretty epic, as I drove back west towards the Orange Cliffs turning south along the edge of an interesting wash that I hadn’t paid much attention to yesterday. Today, re-energized, I stopped to “explore” the intriguing details of erosion at work. The rock wall below was like swiss cheese, a surreal pattern of holes, shadow and light, creating a post-modern sculpture accented with a few random flowers as if mother nature signed her name. Erosion’s handiwork was everywhere in the Maze, and with such variety of effect. Wind and water wear away at rock in different ways, creating deep gorges in some places, spires, arches and fins in others, depending on primarily two things — the type of rock being worn away, and the primary agent of the erosion. The canyons themselves were largely carved by the river waters, but the heavy monsoon rains of summer also scour the landscape, eroding some rock layers more quickly than others to create the strange balanced rocks and towers. The wind does its part, “sandblasting” holes into fins which eventually become arches or smoothing rock walls to an almost shiny flat surface. The history of each part of the landscape is detailed in the park’s Geological Resource Evaluation Report, which makes it clear that no rock is hard enough to resist the forces of weathering and erosion.

Walking through the dry wash, contemplating the composition of holes and crevices as if I was looking at paintings in a museum, I realized how the process that created this amazing landscape would slowly transform it and maybe destroy it in the end, eroding the rock into flat boring nothingness. As much as this place is timeless and eternal, it is also ephemeral, and constantly changing. No two journeys here will ever be alike. I wished I had more time to wander and made a mental note to allocate quite a bit more time for any future Maze trip.

Continuing southwest back towards Flint Cove, I enjoyed the drive. The trail had dried out from the last rain, and navigating the out-and-back part of the leg was simple. I had achieved a certain level of confidence and was moving swiftly, already thinking about the next “unknown” which would be my exit route from the park. I had chosen to make a “loop” rather than go back up via the Flint switchbacks. Though now that I had seen how impressive they were, I almost regretted my decision. Going back up the switchbacks would have been interesting to drive. I had made my original plan based on the idea that I would be able to experience a greater variety of terrain and get to see more of the landscape via the loop. I had a few more miles to go before I would have to commit to one way or the other, and I weighed the options in my head.

There were a few spots on the approach to Bagpipe Butte where I had to pay more attention to the trail, with a series of dry wash crossings and a steep uphill climb ending in a sharp turn that revealed imposing parallel v-ditches, but nothing really technical. I was driving through Big Water canyon along a path that had been used by the cattlemen to take their herds to pasture in the Elaterite Basin. They would move the animals from one area to another depending on the availability of water, and there is actually a spring, known as Big Water Spring, further down in the lower part of this canyon. Apparently at the site of the spring there is evidence of the cowboy camps notably some graffiti etched on the rocks. I did not have time to look for it this trip, but added it to my list for next time.

The terrain was changing again as I reached the crossroad where I would have to make a decision about my exit route. The red rock canyon walls transitioned back into the grey earth that looked like cement. Today’s sunlight brought out the textures and the earth seemed to have more vibrance and color, despite the grey tone. I took a short break to explore a bit while I mulled over my options. An important consideration was how much fuel I had left. With the long distances across the terrain in different directions, and no gas stations for many miles, it was critical to keep track of how much fuel I had and how much mileage I still had to cover. I had carefully calculated all that for my original route, and with the spare ten gallons in the gas cans, I would have more than enough if I followed my plan to exit via Hite. If I changed my route and went back via the switchbacks I would have to get all the way to Hanksville for gas. I had been paying attention to fuel usage during my time out here, only using 4-Lo when I really needed it, and trying to drive in “eco” mode as much as possible. I probably had enough gas to go either way, but caution won out, and I decided to stick to my planned route.

Looking at the “bright side” of my decision, I figured I would at least get to see some different terrain going out this way, and I wouldn’t have to go back over that horrible washboard section on the road near Hans Flat. I turned in the direction of Highway 95, and said a silent “goodbye” to canyon country until next time. There were 33 miles to go this way before reaching the tar road, and I settled in for what I imagined would be a kind of “boring” drive out.

I was pleasantly surprised as I climbed the gentle slope back up the ledge and turned onto an expansive overview of the whole range of landscapes below. I could see all the way to the La Sals. The trail wound along this ledge with a few tight turns accompanied by the most incredible vistas at each twist. A final section wrapped around the cement-like terrain, in an otherworldy hairpin, followed by a moderately steep descent down to Waterhole Flat. Though less “technical” than the switchbacks this route had a drama of its own, and I was glad with my decision to take it.

Back on a nice easy dirt road, I was clearly out of the canyons traveling through a more accessible part of the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. The “recreation area” actually includes 1.2 million acres of golden cliffs, hanging gardens, slot canyons and waterways that cross both Utah and Arizona. It is an administrative section of public lands centered around Lake Powell, a massive reservoir on the Colorado River, which was created by the building of the controversial Glen Canyon Dam. The dam flooded the canyon irreversibly destroying an incredible part of the wilderness. Ironically, the resulting lake was named for the explorer who had inspired so many to make a river trip that is no longer possible. The controversies over public land, wilderness and how to manage it all continue, though they were far from top of mind, as I drove on through the desert appreciating all the incredible landscape we do have access to.

The road wound its way through flat red sandy desert dotted with lush green plants and at one point I thought it would go on forever. I felt myself getting tired and bleary eyed, but I still had to pay attention to the trail because every now and then there would be an unexpected dip or a section that was a bit washed out. The stretch of monotony broke after a slight turn revealed a new landscape and my eyes lit up with renewed interest. In the middle of seemingly nowhere where more rock walls and formations standing on the horizon like yet another ruined acropolis. Of course it was not as “grand” as what I had seen inside the park, but it was quite impressive on its own. And maybe even more so, because it was unexpected and so relatively accessible.

I could park the Jeep and walk right up to the edge of the rock walls and between formations, or wander in the other direction across the flat cracked earth. It was like the desert and the canyons intersected here. Time limited my exploration, as I wanted to get to Hite before dark. I had no specific campsite for the night, and I would have to scout out a suitable spot somewhere. Though Hite was “civilization” it was barely any kind of town — mostly just a Ranger outpost and a gas station. In warmer weather the area might be more crowded with people accessing the lake, but at this time of the year I didn’t expect to encounter many other visitors, and I knew the little general store would be closed. I had identified some possible spots for camping not far from the “town” but really had no idea what the terrain would actually be like, and definitely wanted to set up camp while it was still light. As I got back on the trail, I made another mental note for “next trip” that not all the interesting terrain is “in” the park.

There were just a few miles left to pavement when my “gas light” lit up, warning me to get gas. I was so close to a gas station and really didn’t want to have to start manipulating gas cans and siphoning at this point. I decided to take the risk that the computer was wrong and my own calculations were right. The Jeep’s electronic gas indicator has one flaw — it does not say how “much” gas is left in gallons, rather it computes how many miles the vehicle can travel in the current mode with the gas remaining in the tank. And when the computer determines that the driver should start looking for gas, it lights up, and stops displaying “remaining miles.” I continued towards the road, and the bridge that crosses the confluence of the Colorado and Dirty Devil rivers.

Turning off dirt and onto Highway 95 felt almost strange. But the road was empty and my solitude unchanged. I arrived at the Hite “gas station” a few moments later, relieved that I’d made it. After filling up, I could calculate that I had had a little over one gallon left (and the untouched ten gallons in gas cans). Hite was even smaller than I’d imagined. There was no town, just a sort of “compound” with what looked like one road and a few small houses, the ranger station, and the combination gas station/general store which was closed — though thankfully the self-serve pumps remain functional 24/7. Past the compound and Ranger station there is a campground and public launch ramps, thought I understood that due to the lake’s water levels they were not in service.

The small settlement has been here since the 1880s when Cass Hite found gold in the sands and gravel along the Colorado River, setting off a small gold rush. Hite had learned from the local Navajo that the best spot to ford the Colorado was near the mouth of the Dirty Devil River, 2 miles downstream from the present-day bridge location. He built a cabin and a small store to serve the miners here and a post office was established in 1889, making the “town” official. There was no ferry crossing in those days, just a decent spot to ford in the river. Cass and his brothers operated the crossing and prospectors used this place as a rendezvous point, but the only thing the miners found was fine gold dust too difficult to recover, and mining operations petered out.

Though the area around Hite seemed somewhat deserted, I didn’t really want to camp so close to “civilization” and so after gassing up, I continued a little further south on Highway 95 until the dirt turnoff for Farley Canyon. This canyon opens onto a bay which provides access to Lake Powell. It seemed a perfect spot to camp, and I followed the track in, looking for a decent flat spot to set up camp as the sun was already behind the canyon wall, casting a long shadow across the terrain. Along the shore there are small inlets with smooth slickrock at the edges, remote and peaceful in the middle of sublime canyon scenery. I found a spot where someone had built a fire ring at some point, and though there were some weeds growing up through the rocks, I considered it a decent site to set up camp. Working quickly, I got the tent in place and started my fire as the last light faded into darkness. Enjoying the warm glow of a wood fire again, I kept my small bonfire going under the stars until almost midnight. This was my final night in the wilderness and I wanted it to make it last. As I finally settled in to sleep, I heard the coyotes howling and smiled to myself — everything was perfect.

> CONTINUE: DAY SIX — HITE CROSSING TO MOAB

< BACK: TO GOLDEN STAIRCASE | THE MAZE REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO MOAB >

WHERE WE ARE

The Maze is one of three distinct districts of the Canyonlands national park, located near Moab, Utah. This journey loops north of the town of Moab, then west to Green River and south into the San Rafael desert to reach the Maze district of the park, continuing south into the Glen Canyon Recreation area and then east to Blanding and back north to close the loop.

THE COMPLETE JOURNEY

The Maze Report Home

Gallery: Into the Maze

Day One: Moab to Keg Knoll

Day Two: Keg Knoll to North Point

Day Three: North Point to Golden Staircase

Day Four: Golden Staircase to Maze Overlook

Day Five: Maze Overlook to Hite Crossing

Day Six: Hite Crossing to Moab

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

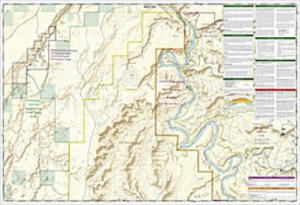

MAZE OVERLOOK / HITE CROSSING / FARLEY CANYON – 60 miles – Estimated drive time 5.5 hours

(click map for larger view of route)

Driving back the way I came for roughly 12 miles, I head west then south over the same terrain I drove yesterday, to the main “junction” of trails near Flint Cove. From there I will begin the southern exit route to the Hite Crossing, rather than returning up the switchbacks. This route is less interesting from a technical driving perspective, however it offers amazingly spectacular views over the canyons all the way to the La Sals. The route follows a high ledge road that turns southward and descends out of the canyons onto a flat open plateau with a nice easy dirt road through some interesting and varied desert terrain heading generally west-southwest for most of the last half of the journey back to pavement. The last leg goes on the tar road across the bridge over the Colorado river into Hite where gas is available, then a final few miles to another dirt access road into Farley Canyon where I decided to set up camp for the night between the canyon walls and the river.

ABOUT GLEN CANYON

The vast landscape of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area contains rugged water- and wind-carved canyons, buttes, mesas, rivers, seeps, springs, and hanging gardens stretching across 1.2 million acres of southern Utah and northern Arizona. It borders Capitol Reef National Park and Canyonlands National Park on the north, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument on the west, Vermilion Cliffs National Monument. the northeasternmost reaches of Grand Canyon National Park on the southwest and the Navajo Indian Reservation on the southeast. Established in 1972 with the dual purposes of safeguarding the land for “preservation” and “recreation.” These sometimes conflicting goals have meant that part of the land has been developed for access to Lake Powell via 5 marinas, 4 camping grounds, two small airports, and houseboat rental concessions, while other areas are more protected. Currently about 588,855 acres (approximately 51% of the total land area) are being considered for wilderness designation. The rugged terrain was shaped by the Colorado River and its many tributaries, including the Dirty Devil, Paria, Escalante, and San Juan rivers, carving through the Colorado Plateau to form a dynamic complex of desert and water environments. The Recreation Area also preserves a record of more than 10,000 years of human presence, adaptation, and exploration. This place remains significant for many descendant communities, providing opportunities for people to connect with cultural values and associations that are both ancient and contemporary.

ABOUT THE JEEP

This journey was made in a 2015 4-door Jeep Wrangler Rubicon sourced from Barlow Adventures in Moab, UT. Traveling alone in such a remote area made vehicle capability and reliability top priority. Barlow’s Jeeps are professionally modified specifically for Moab’s adventurous trails and back roads, with 3″ suspension lifts, 33″ heavy-duty off road tires and extra undercarriage armor. The company has an outstanding reputation within the off-road community for the quality and condition of its Jeeps as well as for the general support provided. The specific Jeep used for this trip was a Hard Rock edition with about 6,000 miles on it equipped with BF Goodrich KO2 tires and in top condition. There would be no worry about mechanical breakdown and the Jeep was more than capable of facing any of the terrain challenges expected on this route.

SPOTLIGHT: THE CHALLENGE OF FUEL MANAGEMENT

Fuel management is an important consideration for any long journey, but for trips into remote backcountry it is even more critical. Gas is not readily available near the Maze, and drivers need to carry enough, not just for their planned itinerary, but to cover unexpected changes in routing. Calculate the expected mileage and know the range of your vehicle. Identify the nearest sources of fuel from the starting and ending points of the journey, and also along any “optional” or “backup” segments. For the loop I initially outlined, the Jeep’s gas tank could hold enough fuel, but there would be no emergency reserve. It was recommended that I carry an additional ten gallons, which would suffice for any detours, re-routing, or extra “wandering” I might do. When carrying supplemental gasoline, make sure to follow safety guidelines. There are different types of gas cans, though one of the most common is the 5-gallon steel “jerry” can (manufactured by Wedco or Wavian). It’s cap clasps securely and is airtight and will not leak. They are now sold with a required funnel, making them CARB compliant (meaning they meet the standards of the California Air Resource Board as well as those of other states). It is also a good idea to monitor fuel usage en route, and drive as efficiently as possible given the terrain. (For more information on gas containers see Carrying Extra Fuel 4-Wheeling)

SUGGESTED MAPS

USGS 1:100,000 topographical maps were used for general routing and orientation, as they provided the best overview of the journey and include the prominent distant terrain features that define the landscape. The journey spans five sector maps (links download full resolution maps from USGS store):

Moab – 1:100,000 topographical map

San Rafael Desert = 1:100,000 topographical map

Hanksville – 1:100,000 topographical map

Hitecrossing – 1:100,000 topographical map

La Sal – 1:100,000 topographical map

For more detail, National Geographic Trails Illustrated maps were used. These printed maps come on reinforced water-proof and tear-resistant material, and include detailed information on recreational trails and points of interest. There are several maps that cover areas included in this journey, though the most critical are the Maze and Canyonlands maps. An important note: be aware that the Maze district map DOES NOT show the Hans Flats Ranger station or the exit to Hite Crossing.

Canyonlands National Park – (210) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 Topographic Map

Maze District: Canyonlands National Park – (312) Trails Illustrated 1:35,000 Topographic Map

Moab North – (500) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 & 1:35,000 Topographic Map

Moab South – (501) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 & 1:35,000 Topographic Map

San Rafael Swell – (712) Trails Illustrated 1:90,000 Topographic Map

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area – (213) Trails Illustrated 1:90,000 Topographic Map

CURRENT MOAB WEATHER

HISTORY: EXPLORATION

The first visitors to Canyonlands came over 10,000 years ago when nomadic groups of hunter-gatherers roamed throughout the southwest. They were followed by the ancestral Puebloan (also referred to as Anasazi) and Fremont people who settled in various parts of the canyons and stayed until sometime around A.D. 1300, when changing weather patterns saw them migrate south. Before the ancestral Puebloans left, other groups appeared in the area, including the Ute and Paiute as early as A.D. 800 and the Navajo sometime after A.D. 1300, though their use and exploration of the Canyonlands area appears to have been minimal. For early European explorers, the Canyonlands were an impediment to travel. In the 1770s, the Spanish priests Escalante and Dominguez circled the area, looking for a route between New Mexico and California. Escalante and Dominguez failed, but trappers and traders from Taos and Santa Fe succeeded. In the early 1800s, the “Old Spanish Trail” became a well-worn route that passed through Moab like U.S. Highway 191 does today. The first Europeans to explore Canyonlands were probably American and French trappers searching western rivers for beaver and otter. Pelts from these animals were in great demand in the east. Official exploration of the Colorado and Green rivers did not occur until 1869, when Major John Wesley Powell led a group from Green River, Wyoming all the way through the Grand Canyon in Arizona. During the three month expedition, Powell mapped the rivers and recorded information about the natural and cultural history of the area. The first Europeans to settle here were members of the Mormon Church. In 1855, Mormons set up a mission in what is now Moab, but conflicts with the Utes caused them to abandon it. The Hole in the Rock expedition–a Mormon mission charged with settling southeast Utah–founded the town of Bluff in 1880. The towns of Blanding, Moab and Monticello were settled shortly thereafter. Most residents made their living as farmers, prospectors or ranchers. (Adapted from Canyonlands People)

GEOLOGY: THE EROSION PROCESS

Erosion is the act in which earth is worn away, often by water, wind, or ice. A similar process, weathering, breaks down or dissolves rock, weakening it or turning it into tiny fragments. Erosion moves bits of rock or soil from one place to another. Most erosion is performed by water, wind, or ice which carries the fragments from the places where they were weathered. Muddy water is erosion in progress, the brown color indicates that bits of rock and soil, referred to as “sediment” are being transported from one place to another. When the wind or water slows down, or the ice melts, the sediment is deposited in its new location. Moving water is the major agent of erosion. Rain carries away bits of soil and slowly washes away rock fragments, while rushing streams and rivers wear away their banks, creating larger and larger valleys. In a span of about 5 million years, the Colorado River cut deeper and deeper into the earth creating many of the canyons in this area. Wind is also an agent of erosion. It carries dust, sand, and volcanic ash from one place to another. In dry areas, windblown sand blasts against rock with tremendous force, slowly wearing away the soft rock. It also polishes rocks and cliffs until they are smooth. Wind is responsible for the dramatic arches and some of the other stunning rock formations found here. (For more information on erosion, see this National Geographic Education site)

ABOUT THE HITE CROSSING

The Hite Crossing Bridge is an arch bridge on Highway 95 that crosses the Colorado River northwest of Blanding, UT. The bridge informally marks the upstream limit of Lake Powell and the end of Cataract Canyon of the Colorado River. It is the only automobile bridge spanning the Colorado River between the Glen Canyon Bridge, 185 miles (298 km) downstream near the Glen Canyon Dam and the U.S. Route 191 bridge 110 miles (180 km) upstream near Moab. The bridge was completed as part of the realignment of State Route 95, which was approved in 1962 due to the construction of Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Powell’s subsequent flooding of the original roadway alignment and the original river crossing in Hite. The bridge was designed by David Sargent, built at a cost of approximately US$3 million, and was dedicated on June 3, 1966. Prior to it’s construction the only way to cross was via ferry. The Colorado River had long beens a major barrier for pioneers and explorers in the region of Southern Utah and Northern Arizona. The first viable crossing point was established in 1873, 100 miles west of Hite, near Page, AZ, by John D. Lee, a Mormon pioneer. Known as “Lee’s Ferry” it remained in service until 1928 when a bridge for US Highway 89A was constructed. A second crossing was Halls Crossing at Bullfrog, 30 miles down river. Hite’s crossing was established in 1883, and was considered the best crossing above Lee’s Ferry. In the early 1930’s Arthur Chaffin moved to Hite, borrowed a bulldozer from the Utah Highway Department and scraped a crude but passable road from Hanksville to Hite and the state built a dirt road from Blanding to Hite thirteen years later. With the improved dirt road as a connecting point, Chaffin built an auto ferry using an old Ford car to power it and a large steel cable to keep it on course. The ferry operation continued until 1964, when the bright steel bridge was built and Utah Highway 95 was paved.(For more information, see this article)

HISTORY: GLEN CANYON CONTROVERSY

The Glen Canyon Dam was completed on Sept. 13, 1963, creating a giant man-made lake in the middle of the desert. It took 17 years to fill Lake Powell, which runs 186 miles long behind the dam providing water for the west, recreational opportunities and turbine generated electricity. Visitors to Glen Canyon National Recreation Area pump some $400 million into northern Arizona and southern Utah annually. Yet, despite the role the lake and dam play as regional economic drivers, they remain at the center of controversy and environmental conflict. In 2013 USA Today reported on the latest chapter of the controversy as environmentalists and Native American communities presented evidence of the ways the dam has damaged the land, the river and sacred sites. The dam project was controversial from the start. Those familiar with Glen Canyon before it was flooded were aware of what the dam would destroy. There were petroglyphs, pictographs, pit houses and rock-walled granaries from Anasazi days that were lost forever in the flooding process. For Native American communities the dam desecrated more than a canyon, it also flooded sacred sites with people. While many sites were completely destroyed by the creation of the lake, others became “tourist attractions.” Rainbow Bridge — the most prominent among them, and the subject of an unsuccessful lawsuit by those who wanted to keep Powell from filling — is a sandstone arc standing 290 feet tall and 275 across. Navajo tradition considers it a “rainbow turned into rock” and the people do not pass under it. However, now the national monument is visited by roughly 200,000 to 300,000 people brought in by tour boat each year. Out of respect for Native American traditions, the Park Service asks people to refrain from walking under the arc, but many tourists do it anyway. The dam has also caused many changes in the ecosystem. Water gushing through the hydropower turbines comes from deep in the reservoir is colder than native fishes such as the endangered humpback chub evolved to withstand. As chubs and other species declined downstream in the Grand Canyon, non-native cold-water trout thrived. The dam also blocked the sand that had flowed through the canyon for ages, altering fish and wildlife habitat while depleting beaches river rafters use. Smaller beaches support less windblown sand to root mesquites and other vegetation, or to cover and preserve archaeological sites from erosion. Growing awareness of damage to the ecosystems led to an environmental-protection act in 1992, mandating dam releases that take river ecology into account. Since then, the Interior Department has sought to restore something of the river’s past characteristics, releasing at least four huge water flushes from the dam to mimic historic floods and churn up sandbars. These efforts created new sandbars and beaches in the short term but eroded a smaller number of existing ones, canceling out any gains in the long-term. Opponents of the dam never liked that it drowned a canyon and changed the river’s ecology, and they see a new opening presented by climate change. The Utah-based environmental organization, Living Rivers, has proposed filling Lake Mead by draining Lake Powell, arguing that a drying climate can’t keep both reservoirs full. Their plan would restore a free-flowing river past Glen Canyon and into the Grand Canyon. But the dam’s supporters point to the necessity of maintaining both Lake Mead and Lake Powell to ensure a water-supply for Arizona and California. They fear a water shortage would spell economic doom for the region. The Bureau of Reclamation concurs, calling Lake Powell “critical to the mix of water-supply options already projected to fall short — barring extensive conservation and reuse efforts — during the coming half century.” (For more on the controversy and environmental effects of the dam, see this Earth Magazine article.)

NOTE: This is the fifth in a series of segments highlighting details of a solo Jeep trip into The Maze district of Canyonlands national park, in Moab, UT. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in October 2015 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads. For more information about the specifics contact us.