A solo trip into one of the most remote places in the continental U.S., the Maze district of Canyonlands national park, offered some interesting challenges and an amazing experience in the solitude and splendor of the wilder desert landscapes. The route chosen for the six day 450-mile journey was almost completely off pavement (and off grid) apart from the initial and final sections of the loop that started and ended at Moab, UT. The primary goal of the trip was to get an overall introduction to the Maze district and work on preparing for logistical contingencies in remote environments.

< BACK: TO MAZE OVERLOOK | THE MAZE REPORT HOME | GALLERY: INTO THE MAZE >

Daylight seeped through the blue fabric of the tent as I opened my eyes to the last day of my journey. I had allowed myself to “sleep in” knowing the drive back to Moab and “civilization” would be an easy one. Outside the sun had not yet come up over the canyon wall, and there was still a morning chill as I began to pack up camp more slowly than usual. Some part of me didn’t really want to “leave” the wilderness behind, though of course I knew I would have a renewed appreciation for the comforts of “modern life” and was looking forward to a long hot shower. Loading the last few items into the Jeep, I watched the sun creep over the rim of the canyon, splashing its light on the rock walls that turned vibrantly red. I suddenly realized I had not spoken to another human being for almost a week.

I had the whole day to make the 150 mile highway drive back to Moab, and decided to do it slowly, incrementally, with a few stopovers en route. My “stops” would add another 50 miles or so, but even with that I estimated it would be no more than five hours of actual drive time. I detoured down to the water’s edge to see for myself this confluence of rivers and man-made lake that had been so controversial. The sunlight warmed my back as I sat on a rock, overlooking the place where the Colorado and Dirty Devil rivers meet. The water went right up to the red walls of the canyon, and it was as if I could see the artist at work, slowly carving out the sedimentary rock. But the water of the lake was calm and slow moving, it’s powers “tamed” by the dam that submerged much of Glen Canyon permanently. The history of the dam and controversy surrounding it is a parable of people’s changing relationship to the land over time.

According to Glen Canyon Dam: Political History, a dam was first proposed after several large floods plagued Yuma, Arizona and the Imperial Valley destroying agriculture in the early 1900s. At that time, building dams was seen as a public good that helped meet people’s basic needs for power, water, and safety from floods. In 1922, after the passing of the Colorado River Compact, states began damming projects, and the Bureau of Reclamation spent several years researching possible sites. Meanwhile, a growing chorus of voices began to call for greater protection of the remaining wild and undeveloped lands of the West. On April 11, 1956, the Colorado River Storage Project authorized the building of Glen Canyon Dam, and the loss of the canyon to the dam and reservoir became a rallying point for conservationists and environmental activists. I had never experienced the lost beauty of the submerged canyon, but I was certainly appreciating the landscape that remained. The sunlight glistened on the water’s ripples and it was quiet. I would have liked to stay longer, but the road was calling me back. I aired the tires back up for highway driving, then headed south on Utah State Highway 95. As the narrow tar ribbon of road followed the contours of Fry Canyon, it seemed like I was the only one out there.

The lonely drive continued through magnificent landscapes for roughly 50 miles, until I reached UT-275, the turnoff for the Natural Bridges National Monument. The park sits high on Cedar Mesa, 6,500 feet above sea level at the junction of White Canyon and Armstrong Canyon, and is centered on the three massive natural bridges that give the monument its name. Cass Hite discovered them here during his 1883 search for gold and the magnificent stone marvels were publicized by National Geographic Magazine in 1904. Four years later, the area was protected with the establishment of the Natural Bridges National Monument.

The Monument was nearly inaccessible for many decades — reaching it required a three-day horseback ride from Blanding — until roads were created for uranium mining and Highway 95 was paved. I didn’t have a lot of time to really explore, but I figured I could enjoy a short hike on one of the trails coming off the scenic drive loop. A hiking trail descends into the canyon from the loop road near each of the bridges, and a longer trail meanders along the canyon bottoms through oak and cottonwood groves connecting the three bridges in one loop hike. I started my walk as a raven’s caw echoed in the silence of the canyon sounding vaguely like a human scream.

Once again I was facing a maze of stone canyons shaped by erosion into a spiral of ledges. The bridges themselves were carved from the white Permian sandstone of the mesa by intermittent streams during periods of flash flooding. The fast flowing water undercut the walls of rock that separate the meanders (or “goosenecks”) of the stream, eventually wearing through to create a new stream bed underneath the bridge. With time, as erosion and gravity enlarge the bridge’s opening, the bridge will collapse under its own weight. There is evidence of at least two collapsed natural bridges within the Monument. Looking at the bridges, they seemed similar to arches, but there is a technical difference — bridges are formed by the erosive action of running water, whereas arches are formed by other erosional forces such as wind.

Over the years, the bridges have been given different names. Hite called them “President,” “Senator” and “Congressman,” and they were renamed “Augusta,” “Caroline” and “Edwin” by later explorer groups. Eventually a decision was made to give them Hopi names, “Owachomo,” “Sipapu,” and “Kachina.” Owachomo, meaning “rock mound”, is named for the large rounded rock mass found on the northeastern abutment of the bridge. Sipapu means “the place of emergence,” an entryway by which the Hopi believe their ancestors came into this world. And Kachina, or “ghost dancer,” is named for its rock art which resembles symbols found on kachina dolls. The Hopi names were chosen because of the similarity between Hopi structures and the Anasazi cliff dwellings found throughout the area. Historically, however, the region generally has more ties to the Navajo and Paiutes people.

The land was first used during the Archaic period, from 7000 B.C. to A.D. 500., by hunter-gatherer groups who left rock art and stone tools behind. Around AD 700, ancestors of modern Puebloan people moved onto the mesa tops to dry farm and later left as the natural environment changed. Around A.D. 1100, new migrants from across the San Juan River moved into small, single-family houses near the deepest, best-watered soils throughout this area. In the 1200’s, farmers from Mesa Verde migrated here, but by the 1300’s the ancestral Puebloans migrated south. Navajos and Paiutes lived in the area during later times, and Navajo oral tradition holds that their ancestors lived among the early Puebloans.

One of the short hikes along the overlook goes to a point known as Horsecollar Ruin, a site that was abandoned about 700 years ago by the ancestral Puebloans. The walk along the desolate sandstone ledge was strange, because despite the natural beauty of the landscape, there were “guardrails” at certain spots, reminding me that I was no longer in official “wilderness.” The trail “ends” at an overlook far from the ruin, which is tucked into a fold of the canyon wall across the way. The ruin is remarkably intact with an undisturbed kiva, though apparently much was removed from the site before it was protected. The wind was blowing a light dust of sand across the canyon, and I felt some primal connection with the mysterious spirits of the past.

As I left Natural Bridges and got back on the highway, I was still thinking about the ancestral Puebloans and their relationship to this harsh and difficult land. The strength and fortitude it must have required just to survive was aspirational. I realized I had learned a lot during my short journey in the wilderness. I continued the lonely drive east on Highway 95. The road was mostly flat and straight through a heavily wooded area and I actually saw some mule deer who seemed surprised by my passing. I was glad they did not run out into the road. They just stood there staring at the Jeep for a few moments before running off, crashing through the brush until they disappeared.

The landscape changed near the intersection with Highway 191, where I turned north and the approach to “civilization” became obvious. Gas stations and strip malls were on the horizon as reached the outskirts of Blanding. Oddly, the small town seemed like a crowded urban metropolis after my week of solitude. And though the “shock” of return was only momentary, I thought it was interesting that I even experienced it after just such a short time “away.”

I decided to make one more stop to revisit Newspaper Rock, the amazing artifact left by the ancestral Puebloans that we saw the first time we ever went to Moab. I would be seeing it from a different perspective now. My journey into the backcountry, which was once their country, had given me some insight into my own relationship to the land. And the rock seemed like a good place to “pay my respects,” saying a silent “thank you” back to the spirit world.

Turning off onto Highway 211, toward the Needles District of Canyonlands, I was driving along the Indian Creek Corridor. This scenic stretch leads to some spectacular rock climbing routes as well as the petroglyph site. Newspaper Rock is well known and easily accessible, so I was not surprised to encounter a few other visitors there. In Navajo, the rock is called “Tse’ Hone'” which means “rock that tells a story.” But this is a visual tale that no one has really been able to interpret. There are over 650 rock art designs from both the prehistoric and historic periods. Contemplating a panel of the curious story engraved on the rock I tried to look for details that “made sense”. A hunter and buffalo, a few other recognizable animals, and many symbols that remained a mystery were collaged in this mosaic of ancient graffiti that only hinted at possible meanings. In the end, I just appreciated the art and the universal human need to communicate, to document, to tell our own stories.

As I left the rock art behind to start the last 50 miles of my journey, the snow capped La Sals to the northeast seemed like stark blue and white silhouettes against the sky. Cows from the Dugout Ranch wandered across the road. I headed north on 191, back to Moab, inspired and full of ideas for the next trip.

< BACK: TO MAZE OVERLOOK | THE MAZE REPORT HOME | GALLERY: INTO THE MAZE >

WHERE WE ARE

The Maze is one of three distinct districts of the Canyonlands national park, located near Moab, Utah. This journey loops north of the town of Moab, then west to Green River and south into the San Rafael desert to reach the Maze district of the park, continuing south into the Glen Canyon Recreation area and then east to Blanding and back north to close the loop.

THE COMPLETE JOURNEY

The Maze Report Home

Gallery: Into the Maze

Day One: Moab to Keg Knoll

Day Two: Keg Knoll to North Point

Day Three: North Point to Golden Staircase

Day Four: Golden Staircase to Maze Overlook

Day Five: Maze Overlook to Hite Crossing

Day Six: Hite Crossing to Moab

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

HITE / NATURAL BRIDGES / NEWSPAPER ROCK / MOAB- 200 miles – Estimated drive time 4.5 hours

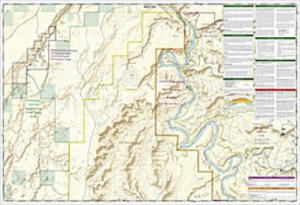

(click map for larger view of route)

Exiting Farley Canyon, I leave the dirt behind and the rest of the day’s journey is all on pavement. From Farley Canyon I take Highway 95 south and east, traveling along Fry Canyon, for roughly 55 miles to a stopover at the Natural Bridges National Monument. From Natural Bridges I continue on Highway 95 eastward for 40 miles to the junction with Highway 191, then turn to the north, through the town of Blanding, and for another 50 miles to the next stopover at Newspaper Rock. The last leg of the day is the final 50 miles north on 191 to Moab.

ABOUT NATURAL BRIDGES MONUMENT

Natural Bridges National Monument was the first site in Utah to be given “national park” status. The main attractions are the natural bridges, accessible from the Bridge View Drive, which winds along the park and goes by all three bridges. While many park features are visible from the overlooks along the scenic drive, the true beauty of Natural Bridges lies just a short walk away from the pavement via moderate hiking trails leading to the base of each natural bridge. Longer loop hikes connect the bridges at the canyon bottom or on the mesa top. There is also a campground and picnic areas within the park. Electricity comes entirely from a large solar array near the visitors center. The park was designated an International Dark-Sky Park in 2007, recognizing that it has some of the darkest and clearest skies in all of the United States. Park elevations range up to 6,500 feet and vegetation is predominantly pinyon-juniper forest, with grass and shrubs typical of high-elevation Utah desert. In the canyons, where there is more water and seasonal streams, riparian desert plants, such as willow, oak and cottonwood trees, thrive. Because the Monument has been closed to grazing for nearly a century, and off-road motorized travel is restricted, Natural Bridges contains extensive areas of undisturbed, mature cryptobiotic soils.

ABOUT THE JEEP

This journey was made in a 2015 4-door Jeep Wrangler Rubicon sourced from Barlow Adventures in Moab, UT. Traveling alone in such a remote area made vehicle capability and reliability top priority. Barlow’s Jeeps are professionally modified specifically for Moab’s adventurous trails and back roads, with 3″ suspension lifts, 33″ heavy-duty off road tires and extra undercarriage armor. The company has an outstanding reputation within the off-road community for the quality and condition of its Jeeps as well as for the general support provided. The specific Jeep used for this trip was a Hard Rock edition with about 6,000 miles on it equipped with BF Goodrich KO2 tires and in top condition. There would be no worry about mechanical breakdown and the Jeep was more than capable of facing any of the terrain challenges expected on this route.

SPOTLIGHT: THE CHALLENGE OF ENDURANCE

Long drive days, complex terrain, navigational challenges, extreme weather and the need to maintain heightened situational awareness can be cumulatively draining over a series of days. And as much as an adventure is exciting and energizing on many levels, it can also be physically and mentally fatiguing at a certain point. Endurance is key to keeping sharp and avoiding sloppiness or careless mistakes that could lead to serious consequences. A solo backcountry roadtrip offers a mental toughness workout that challenges skills and pushes limits. Mental toughness is often confused with physical strength, but these are two separate qualities — someone with great muscular strength may easily crumble when circumstances become too challenging. Toughness is simply the ability to overcome stressful, difficult situations or environments. And like physical strength, mental toughness can be trained. One of the most useful “mental toughness skills” is the ability to handle stress while remaining focused on the task at hand. Another important asset is “willpower” — the mental force to keep going even when we are tired or conditions are adverse. Along with these two, patience and the ability to stay positive complete the “toolkit.” (For more on developing mental toughness skills, see 4 Ways to Accquire Navy Seals’ Mental Toughness)

SUGGESTED MAPS

USGS 1:100,000 topographical maps were used for general routing and orientation, as they provided the best overview of the journey and include the prominent distant terrain features that define the landscape. The journey spans five sector maps (links download full resolution maps from USGS store):

Moab – 1:100,000 topographical map

San Rafael Desert = 1:100,000 topographical map

Hanksville – 1:100,000 topographical map

Hitecrossing – 1:100,000 topographical map

La Sal – 1:100,000 topographical map

For more detail, National Geographic Trails Illustrated maps were used. These printed maps come on reinforced water-proof and tear-resistant material, and include detailed information on recreational trails and points of interest. There are several maps that cover areas included in this journey, though the most critical are the Maze and Canyonlands maps. An important note: be aware that the Maze district map DOES NOT show the Hans Flats Ranger station or the exit to Hite Crossing.

Canyonlands National Park – (210) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 Topographic Map

Maze District: Canyonlands National Park – (312) Trails Illustrated 1:35,000 Topographic Map

Moab North – (500) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 & 1:35,000 Topographic Map

Moab South – (501) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 & 1:35,000 Topographic Map

San Rafael Swell – (712) Trails Illustrated 1:90,000 Topographic Map

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area – (213) Trails Illustrated 1:90,000 Topographic Map

CURRENT MOAB WEATHER

ABOUT THE HORSECOLLAR RUIN

The Horsecollar Ruin Site is a major attraction at Natural Bridges, and one of the best-preserved ancestral Puebloan sites in the area. Named because the doorways to two structures resemble horsecollars, the site was abandoned more than 700 years ago. Its remarkable state of preservation, including an undisturbed kiva with the original roof and interior, is likely due to the isolation of these canyons. The Horsecollar site was uncovered by explorers in the late 1880’s and documented 1907 by an archeological expedition that recommended the establishment of Natural Bridges National Monument. It was forgotten about until Zeke Johnson, the first curator of the Monument, came upon it in 1936. Johnson had crawled up a broken ledge in search of a shady spot to eat his lunch, and was amazed at what he saw. Describing the moment, he wrote, “I saw a ledge full of houses, within 80 yards of the trail over which I have walked for more than twenty years. There is one large kiva with the roof almost complete and a fine ladder standing in the hatchway with the small willows still holding the rungs in place…” The site remains much as he saw it. The roof of the kiva has not been restored and reveals construction techniques used by the ancestral Puebloans. Large roof beams were overlain by smaller branches, then by reeds and thin sticks. This mesh was then covered by a generous layer of mud-plaster. The ladder that once protruded from a hole in the roof has been removed for safekeeping and to prevent curious visitors from climbing inside and causing damage to the structure. Through cracks in the walls, the original fire pit is visible near the center of the kiva. In front of this is an upright slab of rock which prevented air currents from blowing out the fire. Toward the rear wall is a small hole, the “Sipapu” (the gateway through which one’s spirit enters and leaves this world). There is one mystery though — the round “Horsecollar” ruins — no one knows the exact purpose of these unusual structures. (For more information see the NPS article on Horsecollar Ruin)

ABOUT NEWSPAPER ROCK

Located at Indian Creek. along Utah State Route 211, Newspaper Rock is a 200-square-foot section of the vertical Wingate sandstone cliffs that enclose the upper end of Indian Creek Canyon. Covered by hundreds of petroglyphs, it is one of the largest, best preserved and easily accessed collections in the Southwest. This rock displays multiple periods of rock art from cultures dating to 1500 years ago to this century. The older art is attributed to the ancient Puebloan people who inhabited this region for approximately two thousand years, from 100 B.C. to 1540 A.D. The more recent art (lighter in color) is attributed to the Ute people who still live in the Four Corners area. The ancient artists made their designs by carefully scratching the coated rock surfaces with sharpened tools to remove the desert varnish and expose the lighter rock beneath. The petroglyphs feature a mixture of human, animal, material and abstract forms. The exact meanings of the symbols etched into the desert varnish is still not clearly understood. There are over 650 designs including pictures of deer, buffalo, and pronghorn antelope. Some glyphs depict riders on horses, while other images depict past events like in a newspaper. The reason for the large concentration of the petroglyphs is unclear. The rock was designated a State Historical Monument in 1961.

NOTE: This is the sixth in a series of segments highlighting details of a solo Jeep trip into The Maze district of Canyonlands national park, in Moab, UT. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in October 2015 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads. For more information about the specifics contact us.