JoMarie Fecci, of USnomads, joined an international team in a 1,400 mile working expedition to Mongolia, in May-June 2016. The trip, led by Overland Experts founder Bruce Elfström, was providing support for The Mongolian Bankhar Dog Project, an NGO which aims to help save a way of life for the nomadic herders in the Gobi desert while simultaneously protecting a fragile environment. The route was a loop deep into the south Gobi then west into the Altai mountains and back north to Kharhorin before returning east to Ulaanbaatar.

< BACK: TO TSAGAAN SUVARGA | MONGOLIA REPORT HOME | COMING UP: GURVAN SAIKHAN >

From the top of the volcanic outcrop that shelters the Three Camel Lodge it is possible to see nearly 20 miles to the horizon where the Gurvan Saikhan mountains looked dark and uncrossable. Though it seems like a single, solid mass, there is a passage around the Dund Saikhaan Nuruu, or the “Middle Beauty,” where we could cross to go deeper south into the Gobi. We were heading for a barely perceptible “dip” between the peaks to find it.

A forceful wind ripped over the plateau and there was no clear “road,” just lots of criss-crossing tracks going in the general direction. We were already starting to learn that out here tracks almost always go “somewhere.” Occasionally, they may lead to someone’s ger, but the most used ones tend to go where we want to go. The Gobi is sparsely populated and “destinations” are far apart, with big empty spaces in between. The locals drive as directly as they can taking the most forgiving terrain. So, while we might have been tempted to try to drive a straight line to our point, we resisted the urge and picked our way along their tracks. As we approached the base of the mountain, the relief became more apparent and the tracks converged down into a wash that cut between the two peaks. Following its contours, we came out onto a series of small rolling hills that slowly took us up to the top.

Pieces of tattered blue fabric fluttered like a flag atop a small pile of stones in the center of the ridge. Intermingled with the rocks, a tire, some animal horns, a few bottles and other random items seemed to create a dada-esque collage of man-made debris in the middle of nature. This strange sculpture is actually a sacred cairn, known as an “oovo,” and it is home to the spirit of the mountain.

Oovos are common throughout Mongolia. Often found at mountain tops or other high places, they are part of Mongolian shamanic religious tradition, used in worship of the mountains and the sky. During their ceremonies, worshippers place a tree branch or stick in the ovoo and tie a blue scarf to the branch, then they light a fire and make food offerings, followed by a ceremonial dance and prayers.

The oovos are typically made mostly from rocks, but must contain an element of wood (originally all ovoo were made from holy woods). The blue scarves, known as “khadag,” represent Tengri, the sky spirit. And according to the belief, when the wind blows, the essence of the prayer scarf creates an auspicious energy in the area.

Historically, Mongolia was the base of Tengrism, a Central Asian religion with features of shamanism, animism, totemism, and ancestor worship. “Tengri” literally means sky in Mongolian, and some people still pray to “Munkh Khukh Tengri,” or the “Eternal Blue Sky.” In fact, Mongolians often poetically refer to their nation as the “Land of Eternal Blue Sky.” The focus of Tengriism is living in harmony with the surrounding world. Tengriist view their existence as sustained by the eternal blue Sky, Tengri, the fertile Mother-Earth, spirit Eje, and a ruler who is regarded as the holy spirit of the Sky. Heaven, Earth, the spirits of nature and the ancestors provide for every need and protect all humans. By living an upright and respectful life, a human being can keep his world in balance.

The religious traditions can seem mysterious and confusing to outsiders, as elements of Buddhism and Shamanism are often blended, and even agnostics tend to follow the customs. Travellers should pass the oovo on the left, then stop and walk around it clockwise three times, adding a stone or other offering to the pile in order to have a safer journey.

After paying our respects at the oovo, we continued following the contours of the rolling hills down the other side until we were again on the familiar flat gravely desert terrain. Heading due south to Bayandalay we picked up speed, stretching out into a line of moving dust clouds, barely perceptible in all the vastness. The desert on this side of the mountains seemed drier, and more desolate. As the miles clicked by there was only more emptiness, bleached bones, and empty vodka bottles tossed carelessly into the sand–the sole sign of human passing.

The terrain was easy to drive, but navigation began to become more challenging as the distances between “destinations” grew larger and sets of tracks veered off ever so slightly creating an imperceptible “drift” away from planned headings. Periodically we would need to correct after checking our actual GPS position against the map.

Bayandalay finally appeared on the horizon. A thin non-descript line of geometric shapes morphed into the outline of a town as we got closer. We gassed up the vehicles and turned southwest, back into the emptiness. We still had several hours drive to reach the summer pasture lands of our MBDP families near Noyon.

It was hard to imagine how people could live in such harsh surroundings. The Gobi has a climate of extremes, where the temperature has been known to shift 60 degrees Fahrenheit in as little as 24 hours. It can get down to minus-40 degrees in the winter, and as hot as 122 degrees in the summer. Winds sweep across unhindered at up to 85 miles per hour, making it one of the most severe environments on the planet. The Mongolian nomads’ complex and sophisticated adaptation seemed almost magical. For over three thousand years, they have survived out here, almost completely self-sufficient, relying only on their herds to meet their needs.

We were racing the vastness when we saw the strange profile of a lone vehicle stopped in the middle of nowhere up ahead. As we approached we could see it was a van with a disassembled satellite dish on top pulling a cart piled high with an assortment of objects. We stopped to see if the occupants needed assistance.

The husband and wife were busy unloading some baby goats from the van, tying them together so they would not stray. There was no problem with their vehicle. They were simply in the process of moving their family to their summer pasture area. All their belongings, including their ger, were loaded in the van and cart. The traditional nomadic lifestyle discourages the accumulation of “stuff” and prizes creative problem solving.

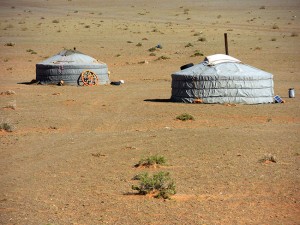

Mobility has been the key to the nomads’ survival, permitting temporary exploitation of resources that were not sufficient to sustain life for very long. Families would move several times a year, and even their homes needed to be portable. The ger was perfected over centuries to enable a household to be set up or taken down quickly. Putting up a ger can take as little as half an hour. The wooden lattice that forms the base of the walls is easy to fold up for transport. And the structure is well-adapted to the seasonal extremes of climate. The round shape can withstand the harsh winds. The felt covering keeps the inside warm in winter, and in summer it can be lifted on the bottom to provide ventilation.

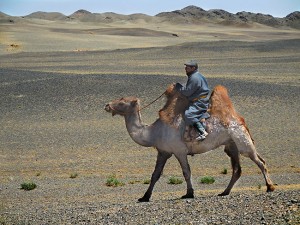

As they continued to unload carpets and a compressor, the man explained to us that the rest of his herds were being led by other family members who would arrive soon. In the distance we could see the surreal parade making its way across the barren desert, the camels being guided by a herder on motorcycle, followed by the sheep and goats pushed along by one herder on a camel and another on horseback with some help from the family dogs.

It was a montage of timelessness and innovation. The way of life here hasn’t changed that much since ancient times, and then again it has. There remains an interdependence between animals, humans and the land, and an independence of family or camp units from the rest of society. Yet they have adapted modern technology to their lifestyles, using solar panels for electricity to power their satellite dishes and TVs. A lot of the herding is done on motorcycle instead of horseback. But the rhythm of the seasons is the same and the skill at improvising solutions has not been lost.

We left the family to their task of setting up household and continued heading southwest. It was late in the afternoon by the time we entered the rocky maze near Noyon uul. Hidden between the dark jagged walls there was a valley with a small stream where semi-wild horses ran freely. It was lush compared to the dusty dry desert we had spent the day crossing. Nestled deep within the series of nested hills a large yellow ger shone in the late afternoon light like a beacon. The local herders had set it up in anticipation of our visit and were waiting to welcome us.

Mongolian hospitality is legendary and after the initial greetings, tea and snacks, we were given news about some local families, their livestock and their dogs. Outside the ger the sheep and goats were gathering on the hillside for the night, protected by the family’s Bankhar.

COMING UP: LEG FOUR — AROUND SOUTH GOBI

< BACK: TO TSAGAAN SUVARGA | MONGOLIA REPORT HOME | COMING UP: AROUND SOUTH GOBI >

WHERE WE ARE

Mongolia is a large landlocked country in east Asia with a strategic location between China and Russia. The country stretches approximately 1,490 miles (2,400 kilometers) from east to west and about 780 miles (1,260 kilometers) from north to south. It is more than twice the size of Texas and just slightly smaller than Alaska. The terrain varies from vast semi-desert and desert plains, grassy steppe and mountains in west and southwest to the extremes of the Gobi Desert in the south-central part of the country. Much of the rugged wilderness is sparsely populated as roughly 72% of the population is concentrated in the urban areas (with almost half (45%) of the total population living in the capital Ulaanbaatar). The official language is Mongol, which is written in cyrillic, with Russian and Turkic also common.

THE JOURNEY SO FAR

This map shows the progress of the expedition team overall as we worked our way clockwise in a loop southwest from the capital. So far we have travelled a rough total of 620 miles. Today’s segment, about 155 miles, is shown in red, the previous segments are rendered in blue.

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

THREE CAMEL LODGE TO GURVAN SAIKHAN: Leaving the Three Camel Lodge we will head southwest towards the Gurvan Saikhan mountains looking for the passage way across. The terrain is easy rolling hills as we gain elevation and then slowly continue back down to the other side where we head due south for roughly 40 miles to Bayandalay. We are again on flat gravelly desert plateau, and after gassing up at Bayandalay we begin to travel southwest in the direction of Noyon for about 80 more miles. Just before reaching the edge of the town, we will turn off into a maze of rocky hills, where we will drive for roughly half an hour longer to reach the summer pastures of the MBDP herding families. Navigation will get more confusing as the routes are less traveled.

CURRENT WEATHER

Ulaanbaatar | Mandalgovi | Bogd | Kharkhorin

TENGRIISM IN MONGOLIA

Tengriism is a shamanistic religion of Central Asia, which was followed by the Huns, Bulgars, Turkic, and Altaic people, as well as the Mongols. It is believed to have begun sometime during the Bronze Age, which lasted from 3,300 B.C. through 1,200 B.C., and is considered ne of the world’s oldest religions. In a complex mixture of monotheism and polytheism, Tengriism believes there is only one supreme God, “Tengri” or the Sky God, who is unknowable, infinite and timeless, but there are also many “demigods.” Tengri created the universe and also created these other demigods or spirits of land, water, earth and the underworld. There are some variations in Tengriism among the many who have practiced it over time. For example, Tengriist Mongolians believe in 99 deities, and Turkish Tengriists only believe in 17. Most commonly, the deities of Tengriism are believed to be Tengri, and sub-deities Yer, Umai, Erlik, Water, Fire, Sun, Moon, Star, Air, Clouds, Wind, Storm, Thunder and Lightning, and Rain and Rainbow. It’s believed respect for the deities will lead to prosperity and well-being. Tengriism a “tolerant” religion, that believes there are many paths to God. This native Mongolian religion is seeing a revival in many parts of the Eurasia and Central Asia.

THE COMPLETE JOURNEY

Waypoint: Ulaanbaatar

Leg One: Ulaanbaatar to Tsagaan Suvarga

Leg Two: Tsagaan Suvarga to Three Camel Lodge

Leg Three: Three Camel Lodge to Gurvan Saikhan

Leg Four: Around South Gobi

Leg Five: Gurvan Saikhan to Hongorin Els

Leg Six: Hongorin Els to Bayan Govi

Leg Seven: Bayan Govi to Lake Oorg

Leg Eight: Lake Oorg to Arvaikheer

Leg Nine: Arvaikheer to kharkhorin

Leg Ten: kharkhorin to Hustai Nuruu

Leg Eleven: Around Hustai Nuruu

Leg Twelve: Hustai Nuruu to Ulaanbaatar

THE MEANING OF COLORS

The color of a “khadag” or prayer scarf is significant. The Blue khadag represents the sky and is the most commonly used type of khadag. It can be given to anyone, even to someone younger than yourself. The White khadag symbolizes milk and purity of a good heart and soul. It is only given to highly respected people. High ranking government officials like the president and the prime minister are typically offered a white khadag. The Yellow khadag is a symbol of knowledge and religion, and so is typically offered to educational or religious teachers. The Red and Green khadags are only used for religious rituals. Red is a symbol of fire and green is for the mother earth. These two colors of khadag are never used to greet people.

TRADITIONAL NOMADIC LIFESTYLE

Mongolian pastoral nomads traditionally relied on their animals for survival and moved their habitat several times a year in search of water and grass for their herds. The herds were the source of food, clothing, and shelter. Boiled mutton was an integral part of the Mongol diet, and wool and animal skins were used to make clothing. Wool was pressed into felt to make rugs and blankets or used for the outer covering of the gers. Households practiced a “zero waste” life style — everything was used — even the dung was collected, dried and used for fuel.

MAP RESOURCES

A great source for route planning and detailed topo maps of Mongolia is Perry-Castañeda LibraryMap Collection of the University of Texas at Austin. You can download 1:250,000 scale sectional topographic maps of most of Mongolia here or 1:500,000 tactical pilotage topos here. Note that these maps are “historical” and marked “not to be used for navigational purposes” but they make an excellent planning tool, as the basic topography does not change. Add to that a current road map from one of the options available here.

THE GER

The word “ger” (pronounced ‘gaire’) literally means “home” in Mongolian. The traditional lodging of the nomadic herder, the ger has a long history. It was first mentioned nearly 2,500 years ago by Herodotus in the first and fourth books of “The Histories,” where he described the Scythians, a nomadic people living in and around the Central Asian region near the Black and Caspian seas. And it probably existed long before, as the recent discovery of a Siberian rock etching that includes a ger dates from the Bronze Age. A tent-like structure made from a wooden frame covered by wool felt, a ger is very easy to collapse and assemble again, and it can be transported by just three horses, camels or yaks. All gers have a roof constructed of straight poles attached to a circular crown, making the roof gently slope downward as it continues out from the center. To put up the ger, the wall sections are tied together to form a sort of cylinder. Then the door is tied in and the roof frame or “tono” is fixed to the two support columns and lifted in the center. Finally the 80 wooden poles get fitted between the tono and the walls. The ger is almost always positioned with the door facing south and there are many traditions relating to it. Custom dictates where specific places people are seated in the ger circle (the zone that encloses and defines the family). Men have the north side of the ger, woman the right or east side, guests the west or, if very important, the north side. People thought less important place themselves in the door way area. Interestingly no other animal is seen as part of this circle, except the dog, whose position is outside the ger and to the right of the door to protect the hearth and its family inside. Even though much of Mongolia’s population has become urban, more than half still lives in this traditional dwelling. Watch this video to see how a ger is moved once it is assembled.

ABOUT THE MBDP

The Mongolian Bankhar Dog Project is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization whose mission is to help slow down and reverse the desertification of the Mongolian Grassland Steppes, and to preserve and protect traditional Mongolian culture. Founded by Bruce Elfström in 2011, the MBDP works with nomadic herders in the Gobi desert to revive the traditional use of the livestock guardian dog known as the ‘Bankhar dog’. For more information, or to donate directly to the MBDP, please go to bankhar.org. To learn more about the origins of the project and its impact in Mongolia, watch MBDP founder and expedition leader Bruce Elfstöm’s TED talk video.

ABOUT OEX:

Overland Experts provides driving and expedition management training programs for the military, humanitarian organizations, professional and recreational drivers. With purpose built trails and obstacle courses at locations in Connecticut, Virginia and North Carolina, they offer comprehensive training in a full range of vehicles and scenarios.

NOTE: This is the fourth in a series of segments highlighting locations and details of the OEX 2016 Mongolia Expedition. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any of the imagery included here, please contact us for permission.