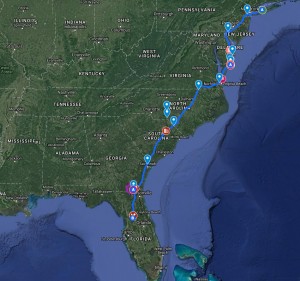

The locations featured in this series were waypoints along a roadtrip route from Long Island NY to Ocala FL. The original trip was done over two weeks in December of 2016 and the round trip route covered roughly 2,500-miles. Most of the journey was on pavement, with the locations featured here being the off pavement highlights. The primary goal of the trip was to explore a section of the Ocala National Forest and work on mapping skills.

< BACK: TO CHINCOTEAGUE | COMING SOON: OCALA >

The skies were still unsettled as I turned into the woods southwest of Folkston GA onto the access road for the Okefenokee Swamp. Dark clouds threatened high above the tall thin trees and the scent of pine was tinged with the smoky odor of fire from a controlled burn not far away. This woodland landscape was not quite what I expected of a “swamp” and I wondered what other surprises awaited.

The Okefenokee was formed over the past 6,500 years by the accumulation of peat in a shallow basin on the edge of an ancient Atlantic coastal terrace. The swamp is bordered by a strip of elevated land, known as “Trail Ridge,” believed to have formed as coastal dunes or an offshore barrier island. Two rivers originate from this swamp. The Suwannee River drains at least 90 percent of the swamp’s watershed southwest toward the Gulf of Mexico while the St. Marys River flows south along the western side of Trail Ridge, then through it, before turning north again and finally east to the Atlantic. Most of the Okefenokee Swamp is included in the 403,000-acre Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge.

The refuge was created in 1937 by president Franklin D. Roosevelt to save the swamp and the wildlife that called it home from attempts at destructive development and commercial exploitation. Roosevelt recognized that the Okefenokee ecosystem is unique in the world and needed to be preserved.

I followed a graded dirt road past the smoldering ash between two stands of majestic longleaf pine. the desolate grey and black of the scorched earth echoed the dark sky, and seemed on first glance in contradiction with the mission of “preservation.” However, “prescribed burns” are an important tool in the restoration process, as the refuge attempts to renew the population of longleaf pine that once covered the entire southeast. Slow to grow, the native longleaf pine was decimated by the logging industry back in the late 1800s and replaced with faster growing types of pine. But certain wildlife species need the longleaf in order to survive. Much of the work done on the refuge today attempts to repair the previous efforts of man to “tame” the swamplands. While the burn may look destructive, it is actually restorative, allowing the fire-resistant longleaf seedlings to germinate.

The pine forest had been unexpected, and the burn counter-intuitive, and I realized I would need to let go of preconceived notions and let the Okefenokee unveil itself on its own terms. To get my “bearings” in this new environment, I started off on the refuge’s interpretive driving loop, known as the “Swamp Island Drive.” The paved loop is a little over 7-miles, with access to a few short hiking trails that together provide an easy introduction to the terrain and its variations, quickly dispelling my ideas about what a “swamp” should be.

Though the popular conception of a “swamp” is a thick murky waterway winding through jungle-like brush, the Okefenokee actually contains several different terrain types. At its center is a vast bog inside a huge, saucer-shaped depression that was once part of the ocean floor. The swamp now lies 103 to 128 feet above mean sea level. Peat deposits, up to 15 feet thick, cover much of the swamp bottom. These deposits are so unstable in spots that trees and surrounding bushes “tremble” when the surface is disturbed. “Okefenokee,” the name given to this area by the Native Americans who lived here, means “Land of the Trembling Earth.”

Native American tribes inhabited Okefenokee Swamp lands beginning as early as 2500 BC. The Timucua-speaking Oconi, who dwelt on the eastern side of the swamp, were the earliest known, and Spanish records between 1602 and 1768 refer to Okefenokee as Laguna de Oconi (Lake Oconi). At least two Timucuan villages and Spanish missions were located in or near the swamp between 1620 and 1656. The legend of “the princesses of the sun” on an island in the center of the swamp is probably rooted in stories of the Timucuan settlements. The legend speaks of a “tribe of beautiful, dark-eyed, maidens known collectively as the ‘Daughters of the Sun.'” These women were said to speak in accents of music and looked like angels. They lived in the Okefenokee on an island that was protected by swirling mists, deep rivers and alligator-filled lakes. Some versions tell of white settlers who became dizzy and unsettled as they searched for these women. Out of nowhere, these angelic-like figures appeared and took them to an island where they nursed them back to health. As soon as the white explorers were well again, they were whisked away in a cloud of smoke. Some later visitors have claimed to have heard “soft laughter” and seen thin, clouded forms whisking through the swamp.

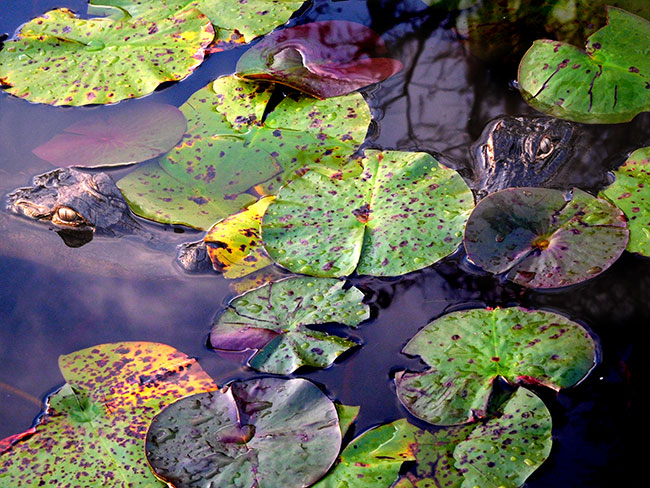

The unsettled weather brought a low fog over some parts of the landscape as I passed a small pond with a tiny island in the middle. The swampland did seem mysterious. Rain started to fall on the dark water, with a sudden violent intensity, the surface rippled in mini waves, and then I noticed the alligator. I had been looking right at him and hadn’t seen him at all. He floated quietly along semi-submerged and not at all bothered by the rain. On the mini-island in the middle a small alligator enjoyed the shower. The alligators are the most “famous” of the refuge’s inhabitants, but the swamp is also home to many wading birds, including herons, egrets, ibises, cranes, and bitterns.

The drive continues as the terrain transitions, following a bit of the history of man’s attempt at taming the swamp. The Chesser Island Homestead is a historic swamp family home and depending on the availability of refuge volunteers it is sometimes possible to visit inside and learn more about pioneer life on the swamp. This homestead was built in 1927, but the family first settled “Chesser Island” in 1858. The first few white families had settled on the southeastern edge of the swamp as early as 1805 while the Okefenokee was still a Creek hunting ground. After the Seminole were forced out around 1838, there was a large influx of pioneers encouraged by an 1820 land lottery. The settlers built log cabins, living off the land, raising some livestock and cultivating small corn patches and gardens. The Chesser family grew sugar cane as a cash crop, they also hunted, kept livestock, tended beehives, and had a substantial garden. The swamp pioneers lived a self-sufficient lifestyle until the railroads changed the dynamic with devastating impact on the eco-system.

The Atlantic and Gulf Railroad from Savannah was the first to reach the rim of the great swamp in the 1860s. Built a few miles north of the Okefenokee it opened the way for sawmills and turpentine stills, store-bought goods and new people. The ring of railroad tracks around the swamp was completed with the opening of a line from Valdosta to Jacksonville in 1898. Industrialization brought jobs and steam transformed both the culture and the landscape. By 1900 the old-growth longleaf pine forest that encircled the swamp was a forest of stumps.

It was hard to imagine this lush landscape stripped and desolate, as I set off on foot through a dense tangle of bay swamp. The Chesser boardwalk trail offers a more immersive experience of the Okefenokee’s habitat mosaic via an easy walk across the rugged landscapes. The area is really a blend of very different terrain. The basin swamp is forested by bald cypress and swamp tupelo trees, beyond are open wet “prairies,” cypress forests, scrub-shrub vegetation, islands and lakes. At a slightly higher elevation, the landscape transitions to thick stands of evergreen oaks, known as “hardwood “hammocks,” where black bears and turkeys feed on acorns and other fruit.

Hammock is the term used in the southeastern United States for stands of trees, usually hardwood, that form an ecological island in a contrasting ecosystem. Hammocks grow on elevated areas, often just a few inches high, surrounded by wetlands that are too wet to support them. Hammocks are not tolerant of fire and tend to occur in locations where fire is not common, or where there is some protection from fire in neighboring ecosystems. Oak hammocks grow as small patches on shallow depressions or slight hills, and are distinct from their surrounding habitats, which are typically woodlands dominated by longleaf pine in the drier more fire-prone areas.

Just a short walk from the trailhead I found myself in a deep thick jungle-like environment of spanish moss draped trees and heavy brush. Looking up it was almost impossible to see the sky through the tangle of branches. This dense dark forest of oak was almost spooky, an ambiance intensified by the haunting hooting of an owl, picked up and echoed by another owl deeper in the woods. I was very glad for the boardwalk on the trail, or I would imagine one might need a machete to get through it. Then, just as I wondered how deeply I was going into a jungle, there was a sudden turn in the trail and it opened up into a “prairie” of low brush and marshland with just a few pole-like remnants of tree and a wide open blue sky above.

The “prairies” are vast areas of non-forested habitat that cover about 60,000 acres of the swamp. They alternate between various wooded sections and are a function of the historical cycle of wildfire and drought. The Okefenokee is a rainfall-dependent system, and when periods of drought occur, the area becomes susceptible to wildfire. According to former Okefenokee Refuge Fire Management Officer, Ron Phernetton, when the water levels were high, it was possible to stop a fire by running it into the water, but when swamp water levels were low, it was impossible to put a fire out once it got into the swamp. Because of the unique physical composure of the swamp land it would burn over an area, then as the swamp was dried out even more, the fire would run back over this same area and burn “the muck” again. It may seem strange that a swamp can burn so out of control for so long, but technically, the Okefenokee is a peat bog.

Peat is formed under very wet conditions, when dead plant material is unable to decay in the flooded environment. This leads to a build-up of partially decomposed organic matter, which over time accumulates in peat domes. These peat domes act as a giant sponge, absorbing water to prevent floods during the wet season, and staying wet to prevent fire during the dry season. However, after a long period of drought, the dry peat is highly flammable. When the water level falls below the level of the peat surface the oily saw palmetto plants that carpet the peat, become a ready fuel source for fires that may have started in the cypress or pine trees as a result of lightning strikes. Even if it rains this just dampens the surface of the peat and the fire can remain smoldering below the surface until eventually the water table rises to extinguish the embers. In areas where the fires burned out vegetation and the top layers of peat, the marsh-like expanses of the prairies are created.

Walking across the open prairie I can still see evidence of the 2011 Honey Prairie Fire, the last massive wildfire to affect the swamp. The fire started with a lightning strike in the southwestern section of the swamp at a location known as Honey Prairie. The initial blaze burned about 1,000 acres and then gradually spread over the entire wildlife refuge area until it had consumed 318,000 acres over the course of three months. Looking at the lush green everywhere around, I could see how the land had been transformed by the fire’s devestation — there were no tall trees here, just a few lonely poles peeking out above the brush. But it was also clear that the wilderness had been rejuvenated. I was seeing and hearing a diversity of wildlife all around. From the Owls Roost observation tower at the trails end the overview of the watery expanse seemed exactly like the thriving ecosystem it should be.

The only way to explore the swamp more deeply was to get down into the water and navigate the maze of canoe trails that crisscross its mesmerizing vastness. The main access point for canoe trails on the east side of the swamp is the Suwannee Canal, built in 1891 as part of grandiose scheme to drain the swamp and create farmland. The plan failed after 4 years and 12 miles of digging. It had proven too costly and difficult. After the Suwannee Canal Company’s bankruptcy, most of the swamp was purchased by lumber companies, who conducted extensive logging operations in the ancient cypress forest from 1909 to 1927. The loggers even ran railroad lines into the swamp, only abandoning it once the cypress stands had been decimated. Some remnants of the logging trains remain visible along the waterways and on the west side of the swamp, at Billy’s Island, there are still some logging equipment and other artifacts from a logging town that boasted 600 residents in the 1920s.

There are 121 miles of canoe trails in the swamp (with 70 miles open to day-use motorboats 10 horsepower (7.5 kW) and under), and seven overnight shelters available in the swamp’s interior. I only had time for a short introductory loop, but was inspired to plan a multi-day kayak/camping outing next time. Visitors can choose to spend anywhere from one night up to four nights (based on trail conditions) camping within the Okefenokee, but should carefully consider the skill levels of the group when deciding on a trail. The swamp terrain can be demanding, and paddling can be slow and strenuous on shallow or narrow trails.

Even a short journey can be incredibly rewarding. Lily-decked water trails reflect the overhanging beauty in a hall-of-mirrors-esque fashion that blurs the edges between land and water. Its a vast wilderness maze that opens out into a montage of islands, lakes, jungles, forest and prairies. The wilderness seemed tame in the late afternoon with the sun finally out in full force. Alligators stretched out on the banks, lazily catching the the last rays of the day’s warmth. Wading birds busy searching for food ignored the passing boat. The haunting silhouettes of swampland vegetation framed the view as the trail wound its way westward.

An amazing assortment of birds could be seen in the trees and bush as the sun began to get lower in the sky. The aura of the swamp was changing with the light. The slow-moving mahogany waters stained by the tannic acid released from decaying vegetation become a solid sheet of impenetrable blackness. A barred owl watches from the shadows of a bare tree while a small alligator peers out of the tall grass unaware of the great blue heron almost right behind him. While adult alligators are at the top of the food chain, juveniles have a lot of predators in this environment, including raccoons, bobcats, and birds like that great blue heron.

The boat distracted the heron and he flew off without incident. The trail was getting narrower and more “swamp like” with strands of spanish moss hanging low over exposed roots. Turning into a tight passage, the vegetation got thicker and the water level was low, making it difficult to move forward for a brief stretch before the waterways intersected in a spectacular clearing between some small islands. These “islands” form when decomposing plant matter on the swamp bottom releases gasses that bubble up to the top, where vegetation attaches itself creating springy, unstable landforms.

The Okefenokee was ready to reveal some of its mystery in this remote and hidden clearing. The lily pads floating on top of the swamp seem to glisten as the sun began to set behind the far off trees. It took me a moment to see the two alligators bobbing their heads between the water lilies. They were practically right under the boat. But after only a few hours on the swamp I had gotten accustomed to their presence and the closeness of the encounter didn’t seem so strange. The sky started to glow with the last rays of the sun and the black water turned to gold for a moment. Then a swash of red, like the brushstrokes of a Van Gogh painting, purple and eventually morphing into the brilliant blue of last light. I looked back towards the water lilies, and the alligators were still there, sharing the swamp’s magical moment with me.

COMING SOON: OCALA NATIONAL FOREST

< BACK: TO CHIONCOTEAGUE | AHEAD: TO OCALA >

WHERE WE ARE

The Okefenokee Swamp is a shallow, 438,000-acre, peat-filled wetland straddling the Georgia–Florida line in the United States. A majority of the swamp is protected by the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge and the Okefenokee Wilderness. The Okefenokee Swamp is considered to be one of the Seven Natural Wonders of Georgia. The Okefenokee is the largest “blackwater” swamp in North America and was was designated a National Natural Landmark in 1974. One of the most remote regions in the American South, the Okefenokee has no roads except around its edges and the only way to explore it is via a network of canoe trails.

THE COMPLETE JOURNEY

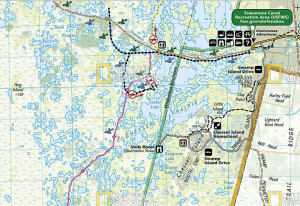

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

GA-25 / GA-110 / HIGHWAY 23 / OKEFENOKEE SWAMP NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE / SWAMP ISLAND DRIVE – 40 miles one way – Plan on a minimum visit time of 4 hours once at the refuge

(click map for larger view of route)

The drive is an easy scenic trip, on paved roads with no navigational challenges to reach the swamp visitor center and drive the interpretive trail loop. From I-95 Exit 14, head west-northwest on GA-25, a lonely road through the woodlands with no services until Woodbine. At Woodbine, pick up GA-110 heading south and west all the way to Folkston, the last town before the entry point to the refuge. If you are planning to stay out in the swamp you should resupply at Folkston, as there are no services beyond this point. From Folkston, take Highway 23, Okefenokee Pkwy, the rest of the way straight into the National Wildlife Refugee. It is roughly 36 miles from Exit 14 to the refuge entry. The Swamp Island Drive is accessed from the refuge visitor center, and is an additional 8 mile loop, with numerous trail heads along the way accessing miles of walking trails. The swamp itself can be visited via canoe, kayak or boat (rentals are available onsite from Okefenokee Adventures) and navigation is fairly straightforward and well-marked on the water trails (guided trips of the swamp are also available). Visitors should stay on the marked “trails” when paddling and not disturb the wildlife. Permits are required for overnight trips and camping along the waterways.

LONGLEAF PINE

Longleaf pine is native to the southeastern United States and is found along the coastal plain in the area from the eastern edge of Texas all the way to the Virginia coast and as far south as central Florida. The Longleaf pine forests of the southeast were once the largest forest on earth, covering over 90 million acres. Today, only about 3 percent — less than 3 million acres — remain. Most of the majestic trees were long ago harvested for lumber and replaced with faster growing species of pine. The Okefenokee NWR has been working to restore longleaf habitats on refuge uplands, thinning some areas, using prescribed burning to maintain an open understory and planting longleaf seedlings. Longleaf pine takes 100 to 150 years to become full size and may live to be 500 years old. The trees naturally prune their lower branches and grow nearly perfectly straight, to roughly 100 feet at maturity. Longleaf pine forests are rich in biodiversity. They thrive in well-drained, sandy soils, and the savanna like vegetation supports many different species. Plants found in this habitat include sedges, grasses, carnivorous plants and orchids. Red-cockaded woodpeckers have become specially adapted to longleaf pine, and will utilize living trees to excavate their cavity. The red-cockaded woodpecker is dependent on mature pine forests and is now endangered as a result of the forests’ decline. Longleaf pine stands also provide habitat for gopher tortoises — a “keystone” species that digs burrows which become habitat for hundreds of other species of animals. To restore these forests, the refuge must conduct prescribed burning because fire is essential to enable the longleaf seeds to germinate and grow. Historically, fire swept through these forests every 1 to 10 years, mostly due to lightning strikes and the trees evolved a unique ecosystem that is highly adaptive to fire. Seeds develop in cones and are dispersed by wind. When they fall to ground, they must come in contact with soil to germinate. Leaf litter and debris prevent the seeds from reaching the soil. Naturally forest fires would clear this ground cover away, but with modern fire suppression, ground cover builds up blocking the seeds from germinating.

PRESCRIBED BURNING AS A TOOL

After many years of fire exclusion, an ecosystem like the swamp, that needs periodic fire becomes unhealthy. Trees are stressed by overcrowding; fire-dependent species disappear; and flammable fuels build up and become hazardous. Prescribed Burning is a safe way to apply a natural process, ensure ecosystem health, and reduce wildfire risk. Perhaps the most important reasons for Prescribed Burning is to reduce naturally occurring fuels within forest areas, lessening the risk of life threatening wildfires. But fire is used by land managers to accomplish other important goals as well. A prescribed burn is an environmentally sound method of preparing an area for seeding or planting because it hastens the return of nutrients to the soil and removes the brush for efficient replanting. Certain pathogens that reduce growth in pines or other species can be controlled or eliminated and the fire destroys diseased foliage, while fire tolerant trees remain undamaged and healthy. Many plant and wildlife species are dependent on periodic fire for their survival or natural restoration. Prescribed burning also minimizes the spread of pest insects and disease, removes unwanted species that threaten species native to an ecosystem, improves habitat for threatened and endangered species, and promotes the growth of trees, wildflowers, and other plants. The burns are conducted by land managers according to “burn plans” developed by specialists. These plans identify – or prescribe – the best conditions under which trees and other plants will burn to get the best results safely. Burn plans consider temperature, humidity, wind, moisture of the vegetation, and conditions for the dispersal of smoke. Smoke impact on roads, residences, and nearby communities are accounted for, and the area to be burned is properly prepared prior to the burn, to ensure the fire is confined within the boundaries. Weather is reviewed for wind, temperature and humidity. Steady winds are critical for success and ideal speeds vary from 3-5 mph in the stand, depending on goals. Optimal temperatures are usually less than 60 degrees, with relative humidity ranges from 30-55%. A qualified team of certified personnel plans and execute the burn, comparing conditions on the ground to those outlined in burn plans before deciding whether to burn on any given day. (For more information: Forest Service Fire Management)

ABOUT THE OKEFENOKEE NWR

The Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge is a 402,000‑acre National Wildlife Refuge located in Charlton, Ware, and Clinch Counties of Georgia, and Baker County in Florida. It is administered from offices in Folkston, Georgia. Nearly 400,000 people visit the refuge each year, making it the 16th most visited refuge in the National Wildlife Refuge System. Founded in 1937, with Executive Order 7593 (later amended by Executive Order 7994), President Franklin Delano Roosevelt established the refuge, designating it as “a refuge and breeding ground for migratory birds and other wildlife.” Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge conserves the unique qualities of the Okefenokee Swamp for future generations to enjoy. The refuge mission includes protecting and enhancing wildlife and its habitat, ensuring integrity of the ecological system, and embracing the grandeur, mystery, and cultural heritage that lead to an enrichment of the human spirit. Because of its varied and unique terrain, the Okefenokee provides habitats for an abundance of plants and animals. There are 621 species of plants growing in the swamp. Animals include 39 fish, 37 amphibian, 64 reptile, 234 bird, and 50 mammal species — notably wading birds, ducks, alligators, bobcats, raptors, white-tailed deer, black bears, and songbirds. Threatened and endangered species found there include the red-cockaded woodpecker, wood storks, and indigo snakes. Okefenokee can be accessed from one of four public entrances: the Suwannee Canal Recreation Area (Folkston), Kingfisher Landing (Race Pond), Stephen C. Foster State Park (Fargo) or Suwannee Sill Recreation Area (Fargo). In addition, a private attraction, Okefenokee Swamp Park, provides access near Waycross, Georgia. A graded Swamp Perimeter Road encircles the Refuge, but it is gated and closed to public use.

WAYS TO EXPLORE OKEFENOKEE

From the open prairies of the Suwannee Canal Recreation Area (Main Entrance) to the forest cypress swamp at Stephen C. Foster State Park (West Entrance), Okefenokee is a mosaic of habitats, plants, and wildlife. There are two major entrances to the Okefenokee and two smaller entraces each with its different facilities and its own special character.

Suwannee Canal Recreation Area (East Entrance) – The is the main entrance managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, located 11 miles southwest of Folkston, GA off Hwy 121/23. In addition to the Visitor Center, which offers a variety of programs to the public, this is the access point to the Swamp Island Drive which winds its way through various habitat of the Okefenokee. The Chesser Island Homestead is located here, and there are hiking trails, including the Chesser Island Boardwalk which goes to the Owls Roost Tower where there is a great overview of the swamp and the Upland Discovery Trail, which winds through pines and palmettos full of woodpeckers, warblers, and white-tailed deer. From this entrance it is possible to access over 100 miles of boating trails to explore the swamp in detail. The refuge’s concession operation, Okefenokee Adventures, offers guided boat trips, canoe/kayak and boat rental, extended tours, overnight guiding on our Wilderness Canoe Platforms, and more. Call Okefenokee Adventures at 912-496-7156.

Stephen C. Foster State Park (West Entrance) – Managed cooperatively between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, this entrance is located 17 miles east of Fargo, off Hwy 177. Boat trails, fishing, motorboat and canoe rentals, guided boat tours, and interpretive programs are all available to visitors. Also, overnight facilities include cabins, tent campsites, and RV campsites are available (reservations required – visit http://www.gastateparks.org/StephenCFoster) or call 912-637-5274 for more information. The west entrance offers access to Billys Island, the second largest island in the swamp and accessible only by boat. Billy’s Island has been inhabited by man for generations. Most recently, the Hebard Cypress Company had a lumber camp on the island in 1918, eventually supporting approximately 600 people.

There are also two “secondary entrances” that have fewer facilities, but still provide access into the swamp itself:

Suwannee River Sill is located eight miles south of the state park. A great place for fishing and observing wildlife, the Suwannee River Sill is open to driving and also has an area to launch small boats/canoes.

Kingfisher Landing, 13 miles north of downtown Folkston on US Route 1/GA Hwy 121. This entrance offers a boat ramp and restroom facilities for day-use and overnight visitors. Access to the Red and Green trails.

SUGGESTED MAPS

USGS 1:100,000 topographical maps were used for general routing and orientation, as they provide the best detail and include the topography that defines the landscape:

Okefenokee – 1:100,000 topographical map

Waycross – 1:100,000 topographical map

For a actual navigation within the area the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge map is a more useful tool. This printed map comes on reinforced water-proof and tear-resistant material, and features detailed topography with shaded relief and vegetation classification, roads including the Okefenokee Trail and Swamp Island Drive, and visitor facilities. Paddling is the best way to explore the refuge in depth, and this map has color-coded canoe trails, trail mileage, difficulty ratings, and charts for overnight canoe trips. Expertly researched and created in partnership with local land management agencies, National Geographic’s map covers the entire park and features key areas of interest including Stephen C. Foster State Park; Suwannee River Sill Recreation Area; Okefenokee Swamp Park; Kingfisher Landing; and Laura S. Walker State Park. Many recreation features are noted as well, including campgrounds, boat ramps, shooting ranges, and areas for wildlife viewing, water skiing, biking, paddling, fishing, and swimming.

ABOUT THE AMERICAN ALLIGATOR

American alligators once faced extinction. “Gator Hunting” had become extremely profitable as reptile shoes, handbags, and belts grew in popularity in the mid-1900s. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service placed the animal on the endangered species list in 1967. Fortunately, the legal protection worked, and just 20 years later, American alligators were taken off the list. Alligators now flourish in the Okefenokee, and are often seen basking on sunny banks or roadsides in cool weather. American alligators live in freshwater environments, such as ponds, marshes, wetlands, rivers, lakes, and swamps. An average male American alligator is 10 to 15 feet long and weighs around 800 pounds. Half of its length is its massive, strong tail. Alligators are generally timid towards humans and tend to walk or swim away if one approaches. Unlike crocodiles, the alligator does not immediately regard a human upon encounter as prey, though it may still attack in self-defense if provoked. The species, scientists say, is more than 150 million years old, managing to avoid extinction 65 million years ago when their prehistoric contemporaries, the dinosaurs, died off. Heavy and ungainly out of water, these reptiles are supremely well adapted swimmers. Even on land they are capable of bursts of speed, especially in very short lunges. Alligators’ main prey are smaller animals they can kill and eat with a single bite. They may kill larger prey by grabbing it and dragging it into the water to drown. The female alligators build nests out of fallen leaves, moss, muck, and other vegetation, keeping it wet by splashing water on it. As the vegetation decays, it produces heat to incubate the eggs. The temperature of the nest during the first two weeks of the gestation period determines the sex of the baby alligators. If the nest is 90 degrees or above, the babies will all be males. If the nest is 86 degrees or below, they will all be females. Temperatures between 86-90 degrees will hatch a mixture of both males and females. It takes roughly 60 to 70 days for the eggs to hatch. After hatching, the baby alligators will start making a clucking sound so the mother will know to uncover her offspring. When hatched, the young alligators will be about 6 inches long. For the first 6 or 7 years, the small gators will grow about 12 inches a year. This is a critical time in the survival of the offspring. Though adult alligators have few predators other than humans, juveniles less than 4 feet long are killed by birds, raccoons, bobcats, otters, snakes, large bass and other alligators. When the weather is cold alligators undergo periods of dormancy, but the don’t actually hibernate. They excavate a depression called a “gator hole” along a waterway to be used when the seasonal temperature falls. In areas where the water level fluctuates, alligators dig themselves into hollows in the mud, which fill with water. These tunnels can be as long as 65 feet and provide protection during extreme hot or cold weather. When they construct alligator holes in the wetlands, they increase plant diversity and provide habitat for other animals during droughts, and are, therefore, considered an important species for maintaining ecological diversity.

WILDERNESS CANOEING

A canoe trip through the Okefenokee offers a unique opportunity to see the swamp ecosystem up-close. Paddle side by side with alligators gliding through the dark brown water as herons and egrets wade among the tall grasses and water lilies. There are 100 miles of canoe trails to explore within the refuge. There are options for day use, overnight and multi-day trips camping on the overnight wilderness platforms throughout the swamp. For overnight camping permits, visit Recreation.gov to view which overnight stops may be available during a time frame you are interested in. Overnight camping permits can be booked 2 MONTHS in advance. Depending on recent rains, water levels in the swamp can vary and overnight platforms can be closed if the water level is too low. Visitors should check with Okefenokee Adventures (912-496-7156) or Stephen C. Foster State Park (912-637-5274) staff before going out on the water trails. There are areas in the prairies where there is very little water and it is easy to get hung up on a peat battery just below the surface. These potentially hazardous areas are difficult to identify visually due to the dark color of the water. Visitors should use their best judgement in attempting to paddle or boat through areas with floating peat and submerged vegetation. Consider the skill level of individuals in your party before choosing a trail. The swamp terrain is flat; there is little fast water and dry land is scarce. Your paddle will be used every inch of the way as you wind through cypress forests or cross open prairies exposed to the sun and wind. Paddling can be slow and strenuous on shallow and/or narrow trails. You may have to get out of your canoe and push across peat blowups, shallow water, or trees. You must plan ahead if you choose a trail that does not return to the same landing. Highway distance between landings ranges from 25 miles to 95 miles.

NOTE: This is the second in a series of segments highlighting destinations along a roadtrip route from Long Island, New York to the Ocala National Forest in Florida. These locations were all stops on a solo Jeep roadtrip made in December of 2016. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in December 2016 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads. For more information about the specifics contact us.