A solo trip on El Camino Del Diablo from Ajo to Fortuna Hills offered some unexpected challenges with beautiful desert scenery and serendipitous surprises along the way. This three-day journey followed the classic ECDD route exiting at Fortuna Mine and provided a quick introduction to the legendary trail as well as to the specificities of operations in the Arizona-Mexico border area. The primary goal of the trip was to get an introduction to the trail and work on navigational skills and logistical contingencies in remote environments.

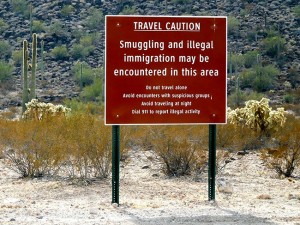

As I turned onto dirt from Highway 85, two Border Patrol vehicles took off at tactical speed down the trail in front of me, kicking up a cloud of dust before disappearing into the desert. The Border Patrol would be the only other people I would see for the next few days, though their presence was somewhat comforting given all the talk about “security” issues related to this trail.

El Camino del Diablo follows the Mexico–United States border very closely for most of its 250-miles through some of the most remote and arid terrain of the Sonoran Desert. The area is a zone of quiet conflict between drug smuggling operations moving product into the U.S. and Border Patrol agents working to keep them out. Occasionally would-be migrants cross this way too, but according to one BP officer I spoke with, this area is so harsh, most prefer to avoid it and attempt to cross in “easier” locations. Entering the trail from the Ajo side there were plenty of “warning” signs alerting travelers to be aware of illegal activities in the area. And while news coverage of some high profile clashes between Border Patrol and the drug operations in recent years have created the impression that it is a real “danger zone,” the journey is a peaceful and magnificent exploration of a legendary route.

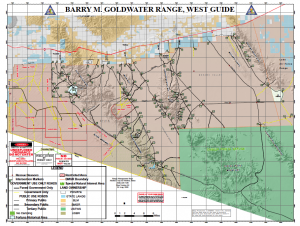

The “classic” El Camino del Diablo Jeep trail run from Ajo westward toward Yuma crosses land administered by several different entities, including BLM land, the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range. A permit is required and the application includes a daunting two-page waiver, entitled, in all caps, “Acknowledgement of Danger; Release and Hold Harmless Agreement” with fourteen separate items to sign off on, but the process is routine and the single permit covers all the differently administrated areas.

Beyond the warning signs, the first section of the trail follows Darby Well road on BLM land. Ahead Black Mountain, the eroded remnant of a basaltic volcano, looms seemingly at the end of the road, but the view is deceptive, and the road curves to pass it beyond the man-made “mountain” of the New Corneilia Mine tailings. Black Mountain and the mountains that were leveled to dig the mine pit are all part of the Little Ajo mountain range, one of a series of ranges that define the topography of the surrounding desert. These mountain ranges will become my guideposts as I drive the trail westward.

While those familiar with El Camino del Diablo say it is possible to drive the entire trail in a single day, most visitors do it more slowly. This was my first time and I was traveling alone, so I decided to do the drive over three days, which I hoped would give me some time to explore some of the more curious “stops” along the way. The trail itself is easy driving along a wide graded dirt road, flat and straight through typical brushy desert. I quickly settled into the rhythm of the sandy soil, scraggly plants, and saguaro cactus set against distant mountains.

In use for at least 1,000 years, El Camino del Diablo is believed to have started as a series of footpaths used by desert-dwelling Native Americans. The area was mainly inhabited by Tohono and Hia C’ed O’odham (federally recognized today as the Tohono O’odham Nation with territory that encompasses portions of Pima, Pinal and Maricopa counties). Tohono O’odham means “Desert People” but the tribe was referred to as “Papago” by Spanish conquistadores and that name was adopted by later English speakers. The Tohono and Hia C’ed O’odham used this trail network to access water, fields, hunting grounds and their sacred places, and shared their knowledge with some of the first European explorers, guiding them across the desert.

The remains of a blockhouse structure behind a rusted metal gate caught my eye and I stopped, surprised that someone could attempt to live here in the middle of such harsh terrain. There was some debris in the yard, but no other evidence of recent inhabitants. I respected the fence line, and came to find out later that the property was the remains of a homestead. At one time a community of Hia C’ed O’odham lived in this area, and though it seems abandoned, the land is still sometimes used by the family for special occasions.

Beyond the old homestead, a large section of the land was ranched by the Cameron family who only retired their grazing allotment in 2005. Looking at the rough desert landscape surrounding me it was hard to believe that cattle or people could thrive here, but this route was used extensively from the 16th to the 19th centuries, as conquistadores, explorers, missionaries, settlers and miners crossed the desert. Though the terrain seems hostile to human existence, El Camino del Diablo was a shortcut, saving at least 150 miles over going by way of Tucson and Gila Bend. The trail followed a geologic corridor of easily passable, though climatically inhospitable, terrain. Between El Camino and the Gila River Trail, roughly 80 miles to the north, lie rugged bands of apparently waterless mountain ranges which block direct travel. To the south of El Camino lie the Pinacate malpais lavas and beyond that, to the Gulf of California, drifting sand and tidal-flat mud.

The distant lines of mountains framed the desert along the edges, like walls containing my world for the length of the journey. I drove parallel to the Black Mountains to my east and then the John the Baptist mountains to my west. Far ahead of me were more mountains. The landscape in between seemed desolate and empty. The road itself was becoming more difficult. Deceptively flat, straight and easy on a map, it was in reality a teeth-rattling washboard, making the drive much slower than I had expected as I tried to spare the Jeep’s suspension from the worst of it.

A little over twelve miles from the start, I cross the first invisible boundary into the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. The monument was established in 1937 to protect and preserve a unique ecosystem against the adverse impacts of ranching and mining interests. The trail cuts through the northwestern corner of the monument, but I didn’t see any of the name-sake Organ Pipe cactus plants, just more of the majestic Saguaros and the otherworldly Chollas.

Driving through Growler Pass the road got a little rougher. The pass cuts between the Growler Mountains to the north and the Bates Mountains to the south. There are nearly a dozen prospect holes in the hills to the north, where hopeful miners once searched for gold, silver or copper. They found nothing of commercial value there but at the Growler Mine site production continued until 1917. That site incorporated four claims over 73 acres complete with its own boarding house for workers. Stocks were sold to distant investors and there was substantial production, reaching 12,000 pounds of copper, 2 ounces of gold and 200 ounces of silver, according to the Arizona Bureau of Mines — however the estimated value totaled just $2,000. There is nothing much left of the mine operations today.

I had taken up a habit of looking at the map, and identifying a mountain in the distance, than driving towards it. This was a good method of “tracking” my position on the map without having to look at it very often, because I knew where I was relative to that specific mountain until I reached it or the road bent away from it. The saguaros stood in a classical desert pose against the far off mountains just like on a postcard, but the Sonoran skyline was interrupted by a strange new addition to the desert landscape — steel poles with blue flashing beacons and an “emergency button” for migrants who want to “give up” and turn themselves in if they are lost and dying of thirst.

![]()

The beacons are an attempt at a humane response to a complex situation. As the security along the border has tightened, more people have tried to cross through the harshest parts of the desert, including an area within the Organ Pipe National Monument. Undocumented border crossers commit to several days of foot-travel in a rugged, inhospitable and perilous desert. Many of the migrants are unprepared for making the journey through this extreme climate. They often do not have adequate hydration and/or food. According to a Christian Science Monitor article, “Most border crossers die from exposure to Arizona’s scorching summer heat in remote desert areas, where they go to escape stepped-up border enforcement.” A notoriously heart-breaking case happened in 1980 when 13 El Salvadoran migrants died of thirst near here, hiding from agents who were trying to rescue them. Another 32 people from the group that included men, women and children, were saved by Border Patrol and park rangers (their story is recounted in the book Escape). The Border Patrol maintains a special unit called Border Patrol Search, Trauma and Rescue or BORSTAR, trained in EMT and rescue techniques who can respond quickly to remote locations and save migrants suffering from extreme heat and thirst.

This section of the desert was wide open and desolate, vast empty spaces spilled out all around me, and I wondered to myself how anyone could even try to cross this on foot (even if there was no border patrols). The harshness of the landscape enforces its own “border” and it seems people have been dying trying to traverse it for centuries. The very name, “El Camino del Diablo” is a reference to this. According to a National Park Service history, the grim name likely dates from the mid-1800s when a steady stream of Gold Rush prospectors used the route westward. Between 400 and 2,000 people died of thirst along the trail, making the Camino the deadliest immigrant trail in North America. One traveler from the late 1800s wrote, “frequent graves and bleaching skulls of animals are painful reminders of unfortunate travelers who died from thirst on the road.” In summer, temperatures here soar to 120 °F (49 °C), and people require two gallons of water a day just to survive.

Luckily I am traveling in January and the temperatures are quite comfortable, with a “normal” average daytime temperature in the 70s (°F) and nighttime lows in the 40s (°F). Still the sun through the windshield is hot, and I have to keep reminding myself to drink even if I am not “thirsty.”

I was fascinated by the different chain-fruit cholla, a cactus I was seeing for the first time. It’s thorns seemed to sparkle gold and silver when the sunlight hit it just right and its “fruit” looks like some kind of bizarre christmas tree decoration. Apparently these fruits are a staple food for the endangered Sonoran pronghorn. I didn’t see any pronghorn in the cholla forest, but I did see a Harris Hawk.

It was already late afternoon by the time I arrived at “Bates Well,” the first waypoint along the trail. A steel-bladed windmill marked the location, and I imagined it was once a kind of “beacon” signaling the presence of water too. I stopped to explore the site, where a few old buildings remain a quiet testimony to a long gone frontier lifestyle. Walking amidst the ruins I tried to imagine what would persuade someone to live out here in such harsh surroundings, where just surviving seemed such an effort.

As with almost all sites of human habitation in the desert, its significance begins with water — nearby springs made this spot a crossroads even in pre-historic times, and later the O’odham village of Juni Kahch was established here. Seasonal water flows from the Growler Wash after monsoons and the presence of five tinajas (basins or depressions that are worn into bedrock that collect rainwater) within a three mile radius meant that this area was one of the few places where water could be found on a reliable basis. The first well was dug here in 1886 in typical Arizona fashion, drilled deep into the ground with a pipe connected to the groundwater which is pumped to the surface. The iconic steel bladed windmill powered the pump delivering the well water into a nearby water tank. The original Bates Well was dug by W. B. Bates, a former Confederate soldier who was part of an influx of American settlers who came to this area after the U.S. Civil War. Many of the newcomers eked out a living raising cattle on the frontier.

Mining and ranching had become important in the region beginning in the mid-1800’s with the Arizona Mining and Trading Company established in 1854 to recover copper ore from the Ajo area and the copper mine at Growler coming online in the late 1880s. The growth of the mining sector stimulated the local cattle industry because the miners needed beef. The number of heads grazing in Pima County increased exponentially from 1,800 in 1870 to 121,000 by 1892. According to one historian’s analysis, “It appears to be a general practice of Desert Cattlemen in all sections of the country around Tucson, Arizona, to run all the range can carry in good years in the hope that during unfavorable seasons, enough of them will survive the drought and lack of forage that they can make up the difference in good years.”

By the early 1900s, there were several extensive ranches in the area including the Gray, Cameron, Childs, Dos Lomitas, Daniels and Miller Ranches. Ajo had been linked with the Southern Pacific in 1916, eliminating the necessity for long trail drives to get cattle to market outside the local area and the cattle ranchers did a thriving business. Bates Well served as one of only a few water sources for the Growler Valley rangeland and when the well caved in a little after 1913 the new owner, Reuben Daniels, dug another nearby, which continued to be called the “Bates Well.” Eventually the property was purchased by the Gray family, one of the dominant ranching outfits in the Sonoran Desert north of the international border.

Described as a feisty, indomitable, rawhide cattleman, the family patriarch Bob Gray was born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1875 and went off to Texas as a very young man to work for a big cattle outfit. By age 17 he had become a seasoned cowboy and married Sara Amanda Cope, a cattleman’s daughter from San Angelo, Texas. They eventually had nine children – five boys and four girls. Sometime before 1912, the Gray family moved to Arizona in a wagon pulled by two mules averaging fifteen to twenty miles a day. They brought some cattle and horses with them and in time Bob set up as an independent rancher near the border with Mexico in what is now Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Gray’s operation started out with roughly 300 head of cattle, a few ranch buildings, Aguajita and Williams Springs, and virtually unlimited, unfenced grazing lands. From that point, he began acquiring local ranches, line camps, and other properties, including Bates Well.

The ranch at Bates Well was one of two main headquarters of the Gray operation and the remains of the homestead offer some insight into the unique style of desert ranching that they practiced. The site contains 12 structures in various stages of disrepair, that together tell the story of daily life in an unforgiving environment. Arizona ranchers relied on the large unfenced range land to overcome the arid climate. Cattle needed to be moved across long distances to fresh grasslands and water sources, so the frontier-border cattlemen set up a series “line camps” within a day’s ride from each other. The line camps were strung out from a central compound, like this one at Bates Well. The main ranch house was the focal point of activity, serving as the operations office as well as the family residence. Ranch houses varied greatly in size, level of workmanship, and architectural styles, often being built from salvaged and miscellaneous materials. Surrounding the main house are a number of auxiliary buildings such as corrals, bunkhouses, barns, and sheds required in the day-to-day work of cattle management. Beyond the main compound there would be a series of line camps distributed according to the locations of watering spots for livestock grazing in the open-range. Line camps were not part of the central ranching complex but were constructed at widespread distances as places where ranch employees could reside while riding the fences, maintaining the windmills, and other tasks necessary on the range.

The Grays continued grazing their herds here even after the area came under the administration of the National Park Service, via a series of grazing permits until the last of the brothers died in 1976. Walking around the site which is preserved though not restored gives the feeling of authenticity you do not find in a “museum.” Bits and pieces of ranch debris are the remnants of lives lived in a dusty crossroad, abandoned in whatever state at some point not so long ago. Though the Grays were the dominant cattle ranchers in the area, their homestead is simple and functional without pretension. The windmill squeaks in the breeze as I peer over a falling fence to what must once have been the corral. The textures of the weathered wood and faded paint predominate. As I walked around the front of the building, the wind blew the door open as if a ghost was inviting me in. I didn’t enter, but did feel a slight shiver up my spine.

Nearby a concrete water trough behind a half-fallen fence I note the very recent addition of plastic water jugs. Those were perhaps abandoned by passing migrants. This old compound would make a good place to stop for the night, though the proximity to a Border Patrol station probably means it is too risky to shelter here, and the people probably just kept moving.

I needed to keep moving myself, if I hoped to get to camp before dark. I had originally planned to get to Thule Well to camp, but I had spent a lot more time making photo stops and exploring than I should have, so I would have to camp at the closer Papago Well waypoint. Back on the trail I tried to keep up some speed, and I just paused briefly at the next invisible boundary line, which separated Organ Pipe National Monument from Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge (Cabeza Prieta, Spanish for “dark (or dirty) head,” refers to a lava-topped, granite peak in a remote mountain range in the western corner of the refuge). There was a small Border Patrol outpost just before the sign indicating the change in administrative zone, and I couldn’t help but think to myself how silly all these invisible boundaries seemed in a desert that was just one giant wide open space.

The character of the landscape changed as I reached the San Cristobal Wash where there is a dense growth of mesquite trees and other brush. The San Cristobal is an ephemeral wash, filled only when there are extreme thunderstorms. When water is flowing it moves northwesterly, running from the Puerto Blanco Mountains to silt flats a few miles south of Dateland, AZ, finally channelling into the Gila River. It seemed “lush” with lots of very welcome shade covering the trail but the sand alternated between very fine and soft in spots, and more washboarding in others. Then in the middle of nowhere there appeared a “road” made of metal plates that looked like some kind of MaxTrax all linked together. These metal “landing mats” were put there to reduce erosion and provide traction for vehicles across what can become an impassable dust bowl during very dry periods. But the mats frequently shift from side to side, leaving “gaps” where vehicles can “fall in” and get stuck. I was careful as I drove over them, also a little concerned that old metal edges might stick up and pierce a tire. Luckily I neither fell into a “gap” nor pierced a tire and after a short bit the “road” just disappeared and I was back on dirt.

Beyond the wash was another forest of cholla cactus, aptly named Cholla Pass. Full of teddy bear and chain fruit chollas it looked like something Dr. Seuss might have drawn. I was tempted to stop and photograph the odd looking plants in the late afternoon light, but the sun was getting lower and the thought of setting up camp in the middle of all these cacti did not seem appealing, so I drove on. The Granite Mountains now framed the edge of my trail to the north while stately saguaros stood in formation in the distance. At first glance they almost looked like people in silhouette and I realized I hadn’t encountered a single person apart from the BP trucks occasionally speeding by in a hurry to or from someplace. The speed seemed out of place here, incongruous in a desert so slow and eternal, a place that seemed to demand a lackadaisical pace with time for curiosity and discovery. Of course the Border Patrol were on a mission or at least a schedule, unlike myself who came with the luxury of time for exploration. But even my time was limited and the setting sun meant I had better hurry on a few more miles ahead.

A little over 35 miles from where I started, a blue flashing beacon stood prominently. Meant for endangered migrants, it was a welcome sight for me, too, as it was placed right near the Papago Well water tank, signaling that I had arrived at “camp” just as the last rays of sunlight splashed everything with neon red. The “official” primitive campground was really no more than an empty space of desert with a few picnic tables chained down. It was cleared of brush and there were some rocks for a fire circle. The well was functional but unlike the Bates Well with the historic homestead, this one had no “artifacts” around it. It had been built to provide water to the Papago Mine in the 1890s and early 1900s but the mine was unprofitable, and the land eventually became property of a rancher, Jim Havins, in the late 1930s. Though Havins built a small cabin and a few other structures, nothing remains but the well itself.

![]()

I hurried to get my tent set up and a small fire started before dark, then sat back and just watched the sky as it changed color transforming the desert into something otherworldly. Vibrant yellows and reds made it look like the sky itself was on fire, and incoming clouds chiseled a rough hewn texture into the surreal canvas before me. The dramatic vista seemed a perfect ending to a first day on El Camino del Diablo and as the temperature began to drop I inched closer to my campfire and savored the magic of the moment.

COMING SOON: TO TINAJAS ALTAS

WHERE WE ARE

El Camino del Diablo (Spanish for “the Devil’s Highway”) is a historic 250-mile (400 km) road which currently extends through some of the most remote and arid terrain of the Sonoran Desert in Pima County and Yuma County, Arizona. In use for at least 1,000 years, El Camino del Diablo is believed to have started as a series of footpaths used by desert-dwelling Native Americans. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, the road was used extensively by conquistadores, explorers, missionaries, settlers, miners, and cartographers. In recognition of its historic significance, El Camino del Diablo was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. It has also been designated a Bureau of Land Management Back Country Byway. The trail crosses BLM land, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and the Barry M. Goldwater Range West.

THE COMPLETE JOURNEY

LEG ONE: AJO TO PAPAGO WELL

LEG TWO: PAPAGO WELL TO TINJAS ALTAS

LEG THREE: TINJAS ALTAS TO FORTUNA HILLS

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

AJO TO PAPAGO WELL – 38 miles –

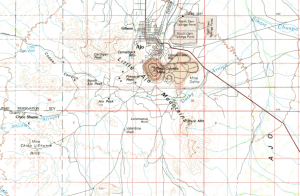

(click map for larger view of route)

Today’s drive starts from the town of Ajo, and turns southwest off pavement onto a long desert trail with no services until Yuma. It is important to fill up before leaving town with gas, water and whatever supplies you need for a minimum of three days in the wilderness. Once on dirt, the trail is a wide and mostly graded dirt road which can be heavily washboarded in sections. Driving is easy on flat straight stretches of well-travelled dirt, with no “obstacles” apart from the washboarding. Navigation is generally straightforward with a few critical junctions that are easy to follow on the map and the route is “marked” by various chains of mountains that serve as clear waypoints. This segment of the journey begins in a more heavily used section of BLM land along Darby Well Road before crossing into the wilderness of the Organ Pipe National Monument and Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge.

DRIVING EL CAMINO DEL DIABLO

A permit is required and obtainable from either the Cabeza Prieta Wational Wildlife Refuge in Ajo (+1.520.387.6483) or the Marine Corps Air Station in Yuma (+1.928.269.7150) and a high-clearance stock 4WD vehicle can normally drive the trail without issue. Before setting out, visitors should contact the refuge visitor center for the latest travel and safety information including sensitive wildlife areas and trail conditions. All vehicles must stay on the El Camino del Diablo, Christmas Pass, and Charlie Bell roads. All other roads and trails are closed and off-limits. There are no services in the refuge and only high clearance and four-wheel drive vehicles (as well as OHVs and motorcycles) are permitted to use the El Camino del Diablo and Christmas Pass roads (all-wheel drive and two-wheel drive vehicles are not allowed beyond Charlie Bell Road). If a road is impassable due to flooding, mud, deep sand or a lawful closure, do not drive off-road to circumvent such areas. For this reason, it is best to be prepared with enough fuel for unexpected turnbacks. The speed limit is 25 mph on the refuge roads and is strictly enforced. Law enforcement officers may occasionally exceed the speed limit while in course of their duties and it is up to visitors to be aware of their surroundings and other vehicular traffic. Visitors are encouraged to camp at one of the designated unimproved campgrounds (no reservations available). No camping allowed within ¼ mile of any game water source and visitors should remove all traces of their presence when breaking camp. Note that the designated “Wilderness Area“ begins 100 feet from the centerline of the road, and vehicles are required to say within 50 feet of that centerline.

SUGGESTED MAPS

USGS 1:100,000 topographical maps were used for general routing and orientation, as they provided the best overview of the journey and include the prominent distant terrain features that define the landscape. The journey spans four sector maps (the following links are to the USGS page for the specified map with an option of free download or purchase of printed map):

Ajo – 1:100,000 topographical map

Cabeza Prieta Mts – 1:100,000 topographical map

Tinajas Altas Mts – 1:100,000 topographical map

Yuma – 1:100,000 topographical map

You must also carry the official “Range Guide” map provided by the Marines when you receive your permit. The “Range Guide” has all the open and closed road designations, and hazard areas clearly marked on a large easy to read map, as well as a list of regulations, and useful information on the back. It is a very good navigational resource (and carrying it is a requirement of your permit).

BORDER SAFETY

Concern for safety in the border region is understandable, but most visitors will not encounter any problems. According to the National Park Service, visitors are unlikely to encounter illegal activity. Migrants and smugglers want to evade detection and therefore try to avoid contact with other people. In rare instances when migrants or smugglers approach a visitor it is usually because they are lost, need water, or are in medical distress. The NPS recommends visitors be aware of their surroundings. Report suspicious activity or people to a ranger, or call 911. Secure parked vehicles and keep valuables, water, and food out of sight. If you should encounter someone or a group traveling cross-country with backpacks, bundles, or black water bottles, do not make contact. If driving, continue to drive and call for help without inviting strangers into your vehicle. If you are hiking move away from them to avoid contact. In reality, the biggest hazards for visitors are not other people but the desert environment.

ABOUT THE JEEP

This journey was made in a 4-door Jeep Wrangler Rubicon sourced from Barlow Adventures in Sedona, AZ. Traveling alone in such a remote area made vehicle capability and reliability top priority. Barlow’s Jeeps are professionally modified specifically for Arizona’s adventurous trails and back roads, with 2″ suspension lifts, 33″ heavy-duty off road tires and extra undercarriage armor. The company has an outstanding reputation within the off-road community for the quality and condition of its Jeeps as well as for the general support provided. The specific Jeep used for this trip was a Rubicon equipped with Mickey Thompson ATZ tires and in top condition. There would be no worry about mechanical breakdown and the Jeep was more than capable of facing any of the terrain challenges expected on this route.

BASIN AND RANGE TOPOGRAPHY

El Camino del Diablo traverses classic basin-and-range topography. It is characterized by abrupt changes in elevation, alternating between narrow faulted mountain chains and flat arid valleys or basins. Mountains reveal their volcanic history in colorful bands or chunks of lavas. As these mountains erode, they form coalescing alluvial fans, or bajadas. Soil and moisture conditions on these bajadas create the ideal habitat for warmth-loving Sonoran Desert plant and animal species. Basin and range topography results from crustal extension (extensional tectonics). As the crust stretches, faults develop to accommodate the extension. For example, in the western United States, this topography is built by a number of normal faults that meet at a basal detachment fault. The basins are down-fallen blocks of crust and the ranges are relatively uplifted blocks, many of which tilt slightly in one direction at their tops due to the motion of their bottoms along the main detachment fault. The normal arrangement in the basin and range system is that each valley (i.e., basin) is bounded on at least one side by one or more normal faults that are oriented along, or sub-parallel to, the range front.

ORGAN PIPE CACTUS NATIONAL MONUMENT

Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument is located in extreme southern Arizona on the border with the Mexican state of Sonora. Established by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1937, and named for a cactus rarely found in the United States, this monument celebrates the life and landscape of the Sonoran Desert in an almost pristine setting. It is a true wilderness where plants and animals live amid dramatic scenery. Sharp volcanic mountains and rocky canyons slope down to forbiddingly hot lowland plains. In this setting you may drive a lonely road, hike a backcountry trail, camp under a clear sky, enjoy the fathomless the night sky, or just soak up the warmth and beauty of the Southwest. The 517 square mile park is the only place in the United States where the Organ Pipe Cactus grows wild. The organ pipe cactus is a tropical plant, and was originally only found in the tropics of Central America, where the warm, wet climate helped the sensitive plant thrive. When the last Ice Age ended, the global climate warmed and the cactus slowly began migrating farther north, arriving in North America 3,500 years ago. The organ pipe cactus is a slow growing plant. On average, the plant will only grow 2.5 inches per year – with greatest growth occurring during the summer monsoons. For the first 10 years, the plant will be no bigger than a few inches, and is prone to trampling by animals or being washed out by heavy monsoon storms. Very few organ pipe cacti will survive until they grow their first stem at 30 years old. Once the first stem is grown, the plant is large enough that it can withstand colder temperatures, drought, and disturbance with greater ease. At this point, their threats are limited to disease, infection, or lightning strikes. An entire plant can live in excess of 150 years. In addition to the park’s namesake, twenty-six species of cactus have mastered the art of living in this environment. Many other types of desert flora native to the Yuma Desert section of the Sonoran Desert region also grow here. This unique biosphere is also home to diverse species of animals who have adapted themselves to the extreme temperatures, intense sunlight, and little rainfall. In 1976 the monument was declared a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO, and in 1977 95% of Organ Pipe Cactus was declared a wilderness area. Organ Pipe NM is nestled between the town of Why to the north, and Lukeville — a border crossing point to Sonoyta, Sonora, Mexico — on the south. The 31-mile southern boundary of the Monument is the border between the United States and Mexico.

CLIMATE

El Camino del Diablo crosses an area of the Sonoran Desert that is generally dry with little rainfall. During any season, diurnal swings of 50°F or more are common, as the dry atmosphere and relatively low vegetation cover facilitate re-radiation of daytime heat into the atmosphere overnight. The regional climate is characterized by what is called a “bimodal precipitation regime.” During the winter, November through March, the skies are abundant with sunshine. Weak winter systems will migrate with high clouds and very little precipitation. Winter precipitation occurs when a low-pressure trough develops over the western United States, pushing the prevailing Pacific storm tracks south over the Sonoran Desert. Strong northerly winds can occur after a frontal passage causing dust storms and reduced visibility. In January, the average daytime high is a comfortable 69°F with an average low of 44°F at night. In Summer the Sonoran is a hot desert with air temperatures routinely exceeding 104°F, and often reaching 118°F. These high near-surface temperatures interact with cool, moist air in the atmosphere to produce the violent thunderstorms of the summer monsoons. As moisture on the soil surface and near-surface air evaporate following a storm, temperatures may drop 50°F or more, often within a matter of minutes. Late summer thunderstorms have the potential to cause flash flooding. Expect roads and trails to turn into fast flowing streams and rivers. Annual precipitation averages from 3–20 inches depending on location, with substantial inter- and intra-annual variability in timing and quantity. The Sonoran Desert’s distinctly different “rainy seasons” — the low-intensity winter (December/January) rains and the violent summer (July/August) “monsoon” thunderstorms — support a broad array of warm- and cool-season flora and fauna, allowing for the amazing life-form diversity found there.

CHOLLA CACTUS

There are more than 20 varieties of Cholla cactus found in the North American deserts. Cholla cactus are found in all of the hot deserts of the American Southwest, with different species having adapted to different locale and elevation ranges. Most require coarse, well-drained soil in dry, rocky flats or slopes. Some have adapted to mountain forests, while others require steep, rocky slopes in mountain foothills. “Cholla” is a generic term for shrubby cacti of the Opuntia genus that have cylindrical stems composed of segmented joints. For propagation the Cholla relies on fallen stems taking root rather than seeds being dispersed. The varieties that have the widest ranges are the ones with joints that most easily snag passing animals or humans. On el Camino del Diablo the most commonly seen are the “Teddy Bear cholla” and “Chain Fruit cholla” also know as the “Jumping cholla.” The Jumping cholla is found throughout the Sonoran desert. A tree-like plant, it has one low-branching trunk and often grows to heights of 4 m (13 ft), with drooping branches of chained fruit. The “jumping cholla” name comes from the ease with which the stems detach when brushed. Often the merest touch will leave bits of cactus hanging on your clothes (The spines are barbed, and hold on tightly — a pocket comb is most useful for removing clusters of spines, or for a single spine use a tweezer). The ground around a mature plant will often be covered with stems that attach themselves to desert animals and are dispersed for short distances. The Teddy Bear cholla is smaller, with a solid mass of very formidable spines that completely cover the stems but look “soft,” leading to its sardonic nickname of “teddy bear”. Typically the plant is between 1 to 5 ft (0.30 to 1.52 m) tall with a distinct trunk that has branches at the top that are nearly horizontal. Lower branches typically fall off, and the trunk darkens with age. Like its cousin the jumping cholla, the stems detach easily and the ground around a mature plant is often littered with scattered cholla balls and small plants starting where these balls have rooted (desert pack rats gather these balls around their burrows, creating a defense against predators).

SHORT HISTORY OF CATTLE RANCHING

Cattle were first brought into Arizona by Don Francisco Vasquez de Coronado on his expedition north from Mexico, 1540-1542. But cattle ranching only got started here in 1696-7 when the Jesuit missionary Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino placed some cattle, sheep, goats, and horses with the Tohono O’odham of Mission San Xavier del Bac and with the Sobaipuri along the San Pedro River at the Quiburi Rancherias. Padre Kino, like many Spaniards, believed that convincing natives to settle around mission sites was key to converting and “civilizing” them. To entice natives away from semi-nomadic lifestyles, he brought new seeds, farming techniques, and most importantly, thousands of livestock. Many natives welcomed the livestock and instruction on ranching and the missions succeeded at diffusing a culture of ranching throughout this part of the Sonoran Desert. However, rather than settling in towns, the Tohono O’odham merged livestock into a semi-nomadic lifestyle, practicing a form of “subsistence ranching.” During wet summer months, the Tohono set up villages in the valleys taking advantage of the rainfall for farming and grazing their livestock. In winter, they moved into the highlands using some of their livestock to supplement meager food supplies. The character of frontier ranching began to change after the U.S. Civil War, with an influx of American settlers. The settlers took to eking out a living in the arid desert through small scale commercial ranching that followed the establishment of mining camps in the area. The industry began to grown larger, with the arrival of the Southern Pacific Railroad through Tucson in 1881, linking the region to the national economy. Prior to the arrival of the railroad, demand for cattle was dominated by the federal government, with contracts to provision forts and Indian reservations, and the local mining operations. The railroad expanded the potential market, and combined with windmill technology that allowed for more animals, brought an explosion of ranchers and cattle speculators from the East Coast. By the 1890s, about 1.5 million cattle roamed in Arizona. This was the period of the iconic “trail drives” to get the animals to market. However, the cattle “boom” faded quickly because the cattle industry did not consider the limits of the land. Over a 20-year period, ranchers overgrazed the pastures permanently changing the landscape. Scrub plants replaced many of the original grasses that never grew back as the topsoil eroded from land that had the vegetation eaten down to the root. Ranchers who wanted to stay in the business had to take a different approach to cattle raising and the open range gave way to stock raising as a modern business enterprise.

ABOUT CABEZA PRIETA NWR

The Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge is located in southwestern Arizona along 56 miles (90 km) of the Mexico–United States border. It is bordered to the north and to the west by the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range, to the south by Mexico’s El Pinacate y Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve, to the northeast by the town of Ajo, and to the southeast by Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. The refuge was originally established in 1939 to protect desert bighorn sheep after the Arizona boy scouts mounted a statewide campaign to save the endangered animal. Today, Cabeza Prieta NWR is home to more than 275 different species of animals and nearly 400 species of plants. A portion of the refuge’s 860,000 acres are open to the public for wildlife related activities including wildlife watching and photography, primitive camping, limited hunting, and environmental education and interpretation. Administered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Refuge offers excellent opportunities to explore one of the most biologically diverse deserts in this country.

WASHBOARD ROADS

Washboarding, the annoying transverse ripples in the surface of dirt roads, is due to frequent traffic moving at speeds above 5 mph. The “washboard” is caused by the repeated bouncing wheels rolling over an initially unrippled surface, essentially “pushing” the sand. At first, tiny ripples form, and then they get larger as more vehicles pass over them. In addition to creating an uncomfortable ride it can be hazardous for vehicles that travel too fast to maintain traction and control. While driving relatively fast over the washboard minimizes the vibration you feel inside the vehicle, your tires are in less contact with the road as they bounce from ridge to ridge at high speed. That means turning and stopping distances are reduced dramatically on an already loose surface. The rapid up and down motion also puts tremendous stress on the suspension which can cause shocks to heat up and fail. The vibration and pounding can also cause bolts to loosen and parts to crack. The better way to drive washboard is to first air down the tires for better grip of the road and use 4-HI to maintain control of the vehicle. Then, while driving “surf” the trail looking for the part of the road with the least heavy washboarding (often the opposite side of the road) and try to get at least one set of wheels on the smoother surface.

THE SAGUARO

A single saguaro cactus can produce millions of seeds in its lifetime. Only a few of these seeds actually sprout. Even fewer grow to maturity. The most successful cactus begins its growth under the shade of a larger plant, commonly called a nurse plant. Almost any plant can become a nurse plant. Shade from the nurse plant protects the delicate cactus seedling from temperature extremes and sunburn. Shaded soil holds moisture longer. Slowly decaying leaf litter adds nutrients and hides the tender young plant from hungry birds or animals. The saguaro cactus seedling grows best in this protected, humid environment and enriched soil beneath its nurse plant. It grows very, very slowly. Estimating the age of a cactus is difficult. There are no annual growth rings, as there are in trees. Rainfall, soil conditions and exposure to sunlight all influence the rate of growth for a saguaro cacti. Long-term scientific studies plus photographic records and other data aid researchers in estimating the age of saguaro cactus. Age and height relationships vary in different parts of the Sonoran Desert. For instance, in a wetter environment such as that on the east side of Saguaro National Park in Tucson, growth rate is faster. A cactus one inch tall may be only six years old. It may reach a full height of 46 feet in merely 173 years.

MILITARY LANDING MATS

The “plank” road section of El Camino del Diablo is constructed with mobile aircraft landing mats, known as Marston or Marsden matting. This standardized, perforated steel matting material was originally developed by the United States military shortly before World War II, primarily for the rapid construction of temporary runways and landing strips. The name came from Marston, North Carolina adjacent to Camp Mackall airfield where the material was first used (Marsden was a misspelling that caught on). Technically referred to as Pierced Steel Planking (PSP), the steel strips were punched with lightening holes in rows, with a formation of U-shaped channels between the holes. Hooks were formed along one long edge and slots along the other long edge so that adjacent mats could be connected. Marston Mats were extensively used during World War II by Seabees and other front line construction personnel to build runways and readily usable surfaces over all kinds of terrain. After the war PSPs began to be used by southeastern U.S. auto racing teams.

SUNSETS

The beauty of Arizona sunsets can be attributed to a variety of factors. Basic physics explains part of it. Sunlight is composed of a spectrum of colors that ranges from violet and blue at one end to orange and red on the other. Particles in the air, such as dust and moisture, can filter out some of those colors. So when we are seeing an orange or red sky, certain particulates are filtering out the blues. Though some people say that pollution is responsible for this “filter” experts disagree, pointing out that some of the most beautiful sunsets are in remote areas of the desert far from urban pollution. In fact, clean air is best for the most beautiful sunsets. Pollution softens the sky’s colors, because the particles of dust and dirt are scattered and are of varying sizes, so the wavelengths sunlight of light passing through the particles are mixed. This lets us see muted tones, more middle of the spectrum. The filtering effect is most pronounced late in the day (or very early in the morning) because the angle of our spot on Earth relative to the sun means the sunlight is viewed through more of the atmosphere. Because of that angle, the light we see may be filtered through particles hundreds of miles away. The sunlight takes a much longer path through the atmosphere with more violet and blue light scattered out of the beam along the way. Finally, the most spectacular sunsets occur when there are at least a few high clouds. Higher clouds are hit by the sun’s rays before they pass through the lower atmosphere, where the air has more particles. So the bright reds and oranges are filtered through at the high cloud’s level and the light is reflected off the clouds.

CAMPING ON EL CAMINO DEL DIABLO

Though this trail could be driven straight through, anyone driving it recreationally will be camping along the way at least one night and more likely two or more. Although dispersed camping is allowed, visitors are encouraged to camp at one of the traditional “camp” spots along the route. A few of these spots have actual “campgrounds” with picnic tables (though no other amenities). Historically “camp” was near a water source for the simple reason that earlier travelers could not carry enough water to make the journey without replenishing en route, however modern visitors should not camp within 1/4 mile of any wildlife water source and should keep vehicles within 50 feet of the centerline of the road. From East to West, the first dispersed camp area is on the BLM land off of Darby Well road just after leaving Ajo. There are “campgrounds” with picnic tables at Papago Well and Thule Well. And there are good dispersed camping spots near Tinjas Altas.

NOTE: This is the first in a series of segments highlighting details of a three-day solo Jeep trip along El Camino del Diablo on the Arizona-Mexican border. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in January 2016 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads. For more information about the specifics contact us.