In preparation for a longer upcoming trans-Saharan journey we conducted a scouting trip in south-eastern Algeria during April 2017. We spent about two weeks traversing roughly 650 miles of desert, primarily off-road. Using the town of Djanet as a base point we looped southeast almost to the Libyan border, and then back north west to the Ihrir oasis. The journey was made in a locally-sourced Toyota Land Cruiser and focused on the UNESCO world heritage sites around Tassili N’ajjer. The primary goal of this mission was to assess terrain, security, driving conditions, logistical concerns and approximate timeframes for a future expedition.

< BACK: TO WANTA BERKA | ALGERIA REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO TIN MERZOUGA >

Leaving the sand dunes of Wanta Berka behind we turned back into the narrow canyons where the camels roamed free. We were looking for a specific cave that contained some ancient paintings as we drove between the towering black walls. Finding the precise location of some of the art here is not an easy task, even with a GPS, as the paintings particularly are tucked away in crevices and caves hidden from view. There’s no way to know which fold of rock offers an entrance to a “gallery” and which simply becomes a blind alley. The landscape itself is fantastical, sculpted by the wind. Rock arches seem to rise from the sand in unlikely places. The work of erosion is on-going here. Blowing sand continues to weather the massive sandstone fins. The formation of arches is a slow process and the unique appearance of a specific arch makes for a convenient landmark. The Lozenge Arch near Moul N’aga is not far from the cave we were looking for.

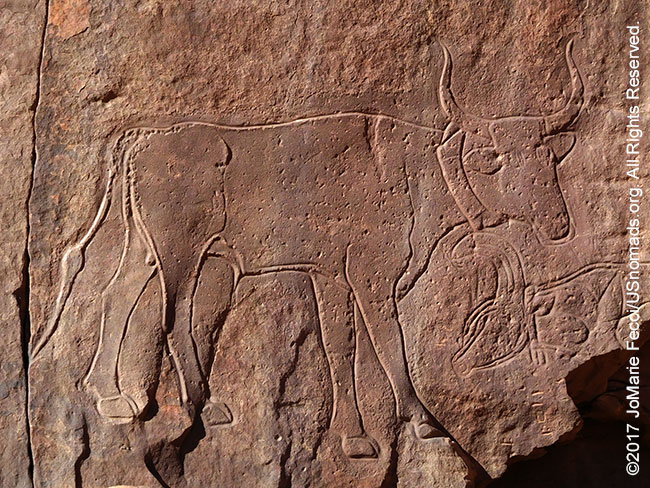

The cave itself was more of an alcove, a shallow shelter, an indentation in the rock wall large enough to offer protection from the elements. The ancient artists made this their canvas, and several scenes by different painters told stories of daily life. The hunt of a mouflon is depicted in great detail. The painting uses red and white pigments and is an elegant expression of a decisive moment. On another section of the wall a tally of animals lined up in rows suggests a herd. These works offer a window onto the shadows of the past, and interpretations vary. The study of Saharan rock art in a systematic way gained momentum in the early twentieth century as art historians and archaeologists attempted to comprehend the meanings implicit in the imagery. Their early efforts to catalog the art eventually led to the protection of theese sites under the UNESCO World Heritage status in 1982.

In a quest to learn more about the world of the ancient inhabitants of the Sahara, researchers defined a structure of distinct periods to make sense of the art in a historical context. They have even analyzed the significance of the locations of the work. For example, the fact that the paintings tend to be located at higher elevations, while the engravings are found on all terrain levels has led some experts to believe the paintings were of a more ritualistic nature. According to this group of experts, the location of the paintings relative to the home territory of the herders suggests a special purpose for the artwork. The people led their daily lives in the lowlands, tending their herds, searching out water and pasture, and then retreated to higher elevations, to hidden locales, for ritual usage. Of course, a less academic, but more practical explanation can simply be that the artists looked for a high point from which to watch over their animals in a protected area of shade, and while they were there, they expressed their creativity in much the same way we might today. No one knows for sure.

Moving from one side of the Tadrart to the other, we had to cross a wall of sand between the rock formations at Moul N’aga. Tall dunes blocked the width of the passage, as if the sand had been blown into the center of the open area to form an impenetrable series of very beautiful berms. The golden orange sand was powdery and blowing slightly, forming the tiniest haze of dust near the point of the crest. We drove parallel to their length looking for what seemed like the best place to cross with our heavily laden Land Cruiser. Though tall, the dunes were fairly straight, and we chose a spot where the slope was not as steep. Taking a good long run up we made it to the peak but bogged down right before cresting, with our front wheels just over the top, but not quite far enough to compensate for the heavy weight of the over-loaded back end.

Maxtrax would come in very handy here but are not widely available in this part of Algeria. Instead local drivers tend to rely on “people power.” Typically trans-Saharan truck drivers travel in a team of three, that includes the driver and two assistants (often a mechanic and apprentice driver), meaning there are always plenty of hands to assist in a recovery. It only took a little push for us to get “unstuck” and we backed down and looped around to build the necessary momentum to make it over the dune on the second try.

The landscape on the other side of the dunes changed dramatically as we entered the Oued In Djaren. Parched white sand was cracked and dry along the bed of what was once a very big river. The In Djaren is very wide in spots and winds its way through the rock walls of the Tadrart, with smaller tributary oueds branching off in all directions. Today it is a “dry wash,” where water flows only occassionaly, but it was once at the center of a thriving culture. The stories left on the walls by the ancient inhabitants are a testament to the existence of its vibrant life-giving waters.

Everywhere around the In Djaren there is evidence of the past. On one wall there is a scene depicting a herd of elephants towering over a small group of people. The elephants are rendered in great detail, while the people are represented in simplified form. Looking out across the desolate emptiness of the barren desert it is hard to imagine jungle animals here. These images belong to the oldest period, typified by the appearance of “big animals.” Tassili rock art is most commonly identified as belonging to one of four chronological periods based on style and content. The oldest is the “big animal” period, an archaic tradition depicting wild animals including elephants, giraffes, and even rhinos, that would be found in a lush green environment. While each engraving has its own character, there is a striking uniformity across those of the same “period.” In the “Big Animal” period the animals are always predominant and are rendered in detail showing the artists’ intimate familiarity with the natural world. The people are small and simplified. The artists were selective in the type of animals they represented, and most animals are shown in profile and without a background or a solid base-line for support which gives the impression that they are floating in space. The exact age of these works are often unknown, but typically they were done well before 4500 B.C. The “cow period” or “bovidian tradition” corresponds to the arrival of cattle in North Africa between 4500 and 4000 B.C. Rock art from this period reflects a changing attitude towards nature and property. Human figures became more prominent, and man was no longer shown as part of nature but portrayed as being above nature, yet able to derive sustenance from it. The cow period is followed by a “horse period” beginning around 2000 B.C. when the first horses appear in the North African archaeological record. The last tradition is the “camel period”, which emerges around the time of Christ. While these traditions are successive, it does appear that earlier ones continued on for varying lengths of time after the appearance of later ones, as the landscape and climate itself was in transition.

The natural realism aesthetic of these artists is an eloquent expression of the relationships between humans and their environment. However much about the artwork and the artists remains a mystery. Archaeologists differ on the question of who made the art, with some crediting the neolithic ancestors of the Tuareg while others argue the Garamantes people of Libya were responsible. Another school of thought says the earliest art was made by indigenous inhabitants who pre-date either of these later groups. For researchers, the inability to confirm the purpose behind the rock art has also proved frustrating. The debate over the interpretations of images and whole rock art panels tends to divide between a religious-symbolic reading versus an ethnographical, historical and anthropological reading. The first Europeans to focus on the region speculated that the artwork was shamanistic in nature. Henri Lhote and Terence McKenna, two of the earliest Tassili experts, considered the art “otherwordly” and inspired by some kind of religious belief. Later scholars have differing opinions on the artists’ intentions.

The “anthopological” interpretation considers the artwork to be simple depictions of daily life, almost “documentary” in nature, connecting the imagery with the lifestyles of the inhabitants as they adapted to changes in their environment. The earliest engravings of the “Big Animal” period, coincide with a subsistence-based hunter-gatherer culture that probably occupied the massifs and the surrounding areas on a seasonal ‘task-specific’ basis. At some point the population became more permanent and eventually pastoral with herds of animals. The introduction of pottery was an important development in their material culture. They used the landscape differently, occupying caves and rockshelters, and their diffuse presence is evident by the frequency of sites used for grinding and sharpening. A fully pastoral culture was flourishing from 5,000-3,300 BC practicing a strategy of “transhumance” (moving in search of pastures) between mountains and lowlands. The population exploited the secondary products of their herds, made a massive use of wild plant resources and had complex rituals. As the climate changed and the terrain began drying up subsistence strategies were redirected towards a high level of mobility, and the inhabitants focused more on their herds while reducing the usage of plant resources.

Looking out across the landscape it was hard to imagine that this desolate empty space had once been inhabited at all. Dry and arid, with cracked earth and blowing dust it seemed eternally inhospitable to human activity. And yet the harsh desert held its own beauty. Rock spires black with desert varnish reached out to the blue sky and sands of two colors met in the middle. We were driving through a surreal maze of dead-end tributaries and hidden messages from the past. The oued In Djaren was like a giant open-air museum, with the work of the rock artists set in a larger “sculpture garden” carved out by the wind and water. We followed the path of the main river bed until it met a field of tall golden sand dunes that rose higher than the cliffs surrounding them.

COMING SOON: THE JOURNEY TO TIN MERZOUGA

< BACK: TO WANTA BERKA | ALGERIA REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO TIN MERZOUGA >

WHERE WE ARE

The People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria, in North Africa is the largest country in Africa and the tenth-largest country in the world. With an area of 2,381,741 square kilometres (919,595 sq mi) it is one-quarter of the size of the entire United States and four times the size of France. Its capital and most populous city is Algiers, located in the country’s far north on the Mediterranean coast. It is bordered to the northeast by Tunisia, to the east by Libya, to the west by Morocco, to the southwest by the Western Saharan territory, Mauritania, and Mali, to the southeast by Niger, and to the north by the Mediterranean Sea. With a population of roughly 38,813,722, Algeria ranks 33rd in population worldwide. The majority of that population, which is a well-integrated mixture of Arab and indigenous Berbers, live in the northern, coastal region. The official language is Arabic though many people also speak French and/or one of the nation’s Berber dialects.

THE JOURNEY SO FAR

This map shows the progress of the team overall as we work our way around the Tassili N’Ajjer region from our starting point in Djanet. We have traveled a total of 162 miles since we began, and the red segment highlights today’s drive.

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

WANTA BERKA TO IN DJAREN – 27 miles –

(click map to view larger image)

Today’s drive winds in and out of the canyon before crossing over the dunes near Moul N’aga. Once on the other side of the big dunes, we continue driving in the wide avenue of the oued In Djaren. Most of the driving is easy on solid sand, but the dune crossing at Moul N’aga can be challenging, as the dunes are quite tall and very soft. Navigation in the early part of the day can be a bit complicated, requiring lots of winding in and out, but once we are in the oued, it is straightforward for the rest of the day.

TERRAIN DETAIL: IN DJAREN

(click image to view larger)

The oued In Djaren is a major “avenue” cutting through the Tadrart. The dry river bed is mostly a cracked white sand and contrasts with the golden sand of the nearby dunes and the black rock walls that surround it. There are stubs of dried plants of a kind found only in this oued. The walls surrounding the river’s path are mostly red sandstone with black desert patina. Leaving the oued the desert becomes a combination of soft blowing golden sand and black and red rock formations once again.

MAP RESOURCES

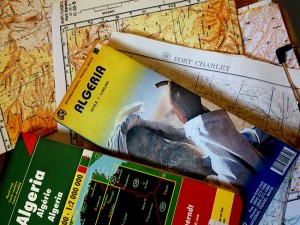

For general planning, a good overview map of Algeria that includes the southeast is this ITBM Algeria 1:2,000,000 scale road map. For detailed navigational planning we used the old Russian 1:500,000 topos that circulate online supplemented by US 1:250,000 tactical pilotage maps from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection of the University of Texas at Austin. Note that these maps are “historical” and marked “not to be used for navigational purposes” but they make an excellent planning tool, as the basic topography does not change. For more on available maps for this part of Algeria and the Sahara generally, see the Sahara-Overland.com map page.

THE WORK OF EROSION

The canyons and rock formations in the Tadrart were shaped by erosion. Erosion is the action of surface processes, such as water flow or wind, that remove soil or rock material from one location on the Earth’s crust and transport it to another. The rock or soil is broken down into sediment which can be transported anywhere from a few millimetres to thousands of kilometres away. While erosion is a natural process, human activities can increased the rate at which it occurs, in some cases resulting in desertification, when the nutrient-rich upper soil layers are completely lost. The Tadrart has primarily been effected by three forms of erosion: wind, water and mass movement. Mass movement is the downward and outward movement of rock and sediments on a sloped surface, mainly due to the force of gravity. It is often the first stage in the erosion process, moving material from higher elevations to lower elevations where other eroding agents such as streams and glaciers can act on it. Some mass-movement processes act very slowly; others like “landslides” occur very suddenly. Water erosion is both downward, deepening the valley, and headward, extending the valley into the hillside, creating head cuts and steep banks. In the earliest stage of stream erosion, the erosive activity is dominantly vertical, the valleys have a typical V cross-section and the stream gradient is relatively steep. When some base level is reached, the erosive activity switches to lateral erosion, which widens the valley floor and creates a narrow floodplain. The stream gradient becomes nearly flat, and lateral deposition of sediments becomes important as the stream meanders across the valley floor. In all stages of stream erosion, by far the most erosion occurs during times of flood, when more and faster-moving water is available to carry a larger sediment load. In such processes, it is not the water alone that erodes: suspended abrasive particles, pebbles and boulders can also act erosively as they traverse a surface. Wind erosion is a major geomorphological force, with two primary varieties: deflation, where the wind picks up and carries away loose particles; and abrasion, where surfaces are worn down as they are struck by airborne particles carried by wind.

PROTECTING THE ROCK ART

The rock art is vulnerable to deterioration caused by climatic phenomena and to damage caused by humans. The human threats include tourists who wet paintings to make them easier to photograph, insurgents who take refuge in caves and use the art for target practice and looters who use chisels, sledgehammers, chain saws, jackhammers and crowbars to pry the artwork loose, often destroying or badly damaging it in the process. The UNESCO World Heritage status includes a mandate to protect and preserve these fragile sites — a task that is not always easy given the contemporary geostrategic challenges and the location of the artwork. For the Tassili N’Ajjer region, the Algerian government has created a special framework known as the cultural heritage law (Law 98-04 on the Protection of Cultural Heritage). The Ministry of Culture established a “cultural park” to protect the whole geographical space in which both cultural and natural heritage sites are interlinked. The concept includes steps to conserve not just the prehistoric art, but also the existing urban fabric of the towns surrounding it. The programs currently underway respond to the challenges of conservation in extreme weather conditions and also to the education of local residents in the sustainable use and management of the area. Tourism, which generates income and jobs for the local population, is strictly controlled to ensure protection of these important resources.

CREATING THE ROCK ART

The engravings and paintings found in the Tassili region were made by artists using primitive tools and a variety of techniques. The engravings were created by chiseling the stone. Some artists chipped away the patina that covers the rock face, revealing the image etched into the rock layer beneath. They used stone chisels that had been hammered to a point. Some of the chiseled grooves are more than two inches deep which has helped the artwork endure in the face of desert sandstorms and winds. The paintings were usually done with paint made from locally available minerals such as ocher (red and yellow iron oxide), white clay and charcoal. Blood, fat and urine may have been used as binders. In many cases the colors are still vibrant after millennia of exposure to desert heat. The paints were sometimes applied with brushes made of feathers or animal hair. Often new paintings were superimposed on top of old ones. Scientists using infrared detection devices have counted up to 12 superimposed layers painted during a period of around 2,000 years at individual sites. It is not known why certain locations were selected for multiple paintings. Perhaps the sites had religious significance or maybe their surfaces and light were particularly good.

TIPS FOR 4×4 SAND DRIVING

Driving in Saharan sand dunes has its own challenges. Here are a few tips from local professional drivers.

Air Down: To grain additional traction on soft sand air down more than usual. In some situations some drivers go down as low as 8 PSI, but usually somewhere around 15 PSI is ideal. However, be careful about airing down too much if the area also has sharp-edged rocks.

No Brakes: Do not use brakes on sand. When coming to a complete stop, try to release brakes before stopping, so the tires can sit on top of the sand. Braking causes a sand “berm” in front of the wheels making it likely the vehicle may need to be dug out or have to reverse out.

Parking: Always stop the car on a slope in a nose-down position, so it will be easy to regain momentum when starting again. Make sure the vehicle’s longer axis is aligned with the up-down direction of the slope (so driver should be looking straight down). Never trust hand-brakes to hold the vehicle. Always shift to first once the engine is off, before leaving the vehicle (in manual transmission). It is also good to secure the vehicle by chocking the wheels with rocks.

Getting Unstuck: Assess the situation and look for slopes that can help the recovery as well as areas of more solid sand to try to recover to. If the vehicle is not very stuck, try putting it in 4L to get the maximum torque and slowly press the gas pedal. If it is more stuck, remove the sand from in front of your wheels if you are going forward or from behind your wheels if you are trying to go in reverse. Also make sure to remove sand from differentials or other key components on the underside, so as to reduce friction. Depending on the situation, you may also want to further deflate the tires. If you have Maxtrax or sand mats, deploy them appropriately. In the Sahara, drivers typically do not have Maxtrax, but instead rely on the help of colleagues to push the vehicle physically. Once the vehicle is unstuck, point the nose towards a slope or towards more solid sand and accelerate slowly. (Trying to accelerate too quickly will just dig the vehicle back in).

PSYCHOLOGY OF ROCK ART

No one knows what thoughts or beliefs motivated the artists of the Tassili region, but some experts find a universal link between ancient rock art all over the globe. They point to a common human psyche to explain why analogous motifs and symbols can be found in places very far apart. According to Dr. Ilse Vickers of the Bradshaw Foundation, these archetypal patterns are rooted in the depth of the human psyche from where they spontaneously arise when the conscious mind lets loose the imagination. When trying to interpret the rock art, viewers should not think of these early artists as a primitive ’them’ versus a modern ’us’. The supposition that so-called ‘primitive’ man thought or experienced his world in a way that was significantly different from us is not based on fact. The human mind was the same then as it is now. Ancient man’s thoughts and feelings did not significantly differ from our own and he had astonishing creative talents. His imaginative, intuitive skills were developed to such a degree that we can say with confidence that he had a belief system that was sophisticated, and far more developed than has hitherto been assumed. The difference is in the way we experience our world. The ancients lived in a primordial state and in total harmony with their surroundings. They were more “tuned in” to the environment and able to hear the ‘voice’ of their mountains. Primitive man had a mystical relationship or identification with his world. These artists’ imaginative pictorial images are a creative expression and their “meaning” will always remain a mystery. As soon as we try to dissect the rock art, saying it either means this or that, its true meaning is lost: its treasure lies in its totality. Psychologically speaking, the rock art is not a matter of the intellect but a psychic experience which expresses itself in symbols.

NOTE: This is the fourth in a series of segments highlighting details of a two-week scouting trip in the south-east of Algeria. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in April 2017 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads with a local Djanet-based team. For more information about the specifics contact us.