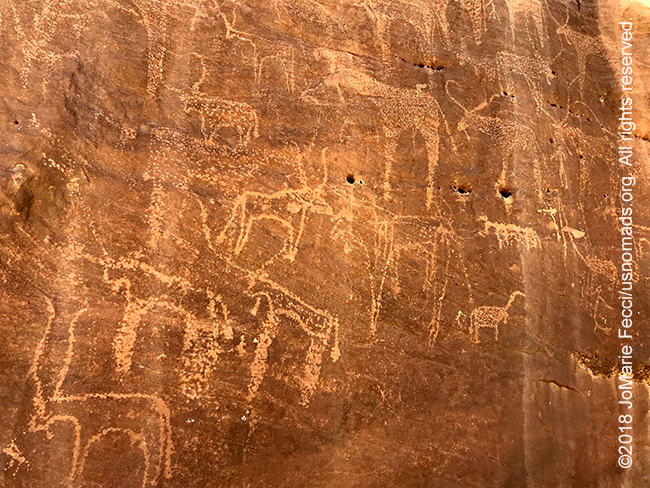

KARIMA, SUDAN (9 April 2018) — This morning’s “surprise” was a gallery of rock art hidden in plain site in a wadi not far from Wawa where we spent the night. The wadi itself was seemed to be just an ordinary dry wash passing between some rocky banks, but further inspection revealed the place to be quite special. There were probably thousands of engravings on the surrounding boulders and rock walls.

We stopped to explore, climbing up and over the rocks chasing the story etched on each one, frames of a storyboard from across the ages. Many of them were rough-hewn and simple in comparison to the rock art examples from the Tassili, but the fact that they were here in one small place had some kind of meaning. Why here? It was another question that would remain unanswered apart from what we could only speculate. While I was photographing, Sami was exploring and actually discovered a depiction of an animal he had not seen here before, and he marked the spot with a small rock cairn so he could find it again easily.

It would have been easy to pass the whole day here among the rock art, but we needed to move on, as we had a long day’s journey ahead. We had to get to Karima tonite so that we would have a little bit more time to spend at the most important archeological sites of the Meriotic Kingdom. And we would make a short stop at the Third Cataract of the Nile. With the daylight “clock” ticking, we left the wadi with so much unseen, and got back to the tar road heading south past the gold miners. We didn’t stop until we reached the Third Cataract near the base of a hill with an old fortress on top. From there we could look down to the Nile and see the whitewater spilling over the rocks. The Cataract was not exactly a waterfall as I had expected, it was really more of a rocky fast moving section of river with some islands in between. And down there in the middle of it were a few men with small boats, navigating its quick currents with careful skill.

I watched their struggle for a little while then went back down the hill where a bus load of tourists had just pulled up. The group was on a multi-country tour of the region in a modified overlanding “bus” that could handle rough driving conditions. They didn’t look happy to be hiking up the hill in the heat, and I wondered what kind of trip they were on and why they would travel this way. Their guide turned out to be one of Sami’s colleagues whom I had met at the museum in Khartoum. He told us that this kind of tour group was not very fun to work with, and that he was only with them for a segment of their journey. They would be going all the way to Egypt. I could see the charm in the idea of their journey, but the reality of it didn’t seem very attractive. Either they needed more time or perhaps a smaller group. In any case we left them to the Cataract and continued on our way back to the Fish restaurant where we stopped for our own lunch before attacking the rest of the road to Karima.

The highway drive was tedious without stopping and we were all getting quite bleary-eyed. I tried to take some photos as Gammal drove, but the flat and non-descript desert terrain along this part of the drive was uninspiring and the heat was sapping my energy. For the first time since I began my journey in Sudan I was wishing we would finally “arrive” somewhere. And that feeling was very unusual for me.

Eventually we started to reach the outskirts of a major town and I quickly realized that Karima was more of a “city” than a “town.” It had big buildings and a bit of sprawl and a more “urban” feel than the towns we had been in before. The road also became “bigger” with heavier traffic. This route was the main artery for travel from the north and east, with many commercial trucks moving goods from the port. No longer were we seeing the trucks of camels being sent to Egypt instead there were containers coming off ships and destined for Khartoum. And then, on the side of the road with no fanfare, there were pyramids!

These were tall and narrow pyramids, very different in style from the ones of Egypt, but prominent in the landscape and regal looking against a desert background. Behind them was Jebel Barkal, a mountain that had some kind of holy significance in the past, and a mystique even now. The guys wanted me to climb it at some point, but I was resisting. Seeing it now, I realized it would take me an entire day to climb. We stopped for a short photo op at the pyramids, but Sami wanted us to move on quickly before we lost daylight as he had something to show me.

He had been working in this area recently, at the UNESCO site currently being excavated and prepared for visitors. We went to the locked gate and he opened it and we just walked in. Of course it could be easily accessed without a key from the village surrounding it, and locals were walking through the area on their way to or from somewhere, but we came in the “front door.” The site had a number of important tombs, some still standing and others crumbled to piles of rubble. Sami knew all about the history of this place and explained about a tomb for horses and how the ancients cared for their horses and all these other details that he knew from his work at the site. He explained the difference between Egyptian tombs and Nubian tombs and the pyramids that concealed each. The entryways for the Nubian tombs were far from the pyramids themselves, and they would go down into the earth below the pyramid, whereas the Egyptian tombs had entryways built into the pyramid itself.

We visited some of the exterior sites and then we went into a tomb that had just recently been excavated and was not yet open to the public. This tomb was “unfinished” and did not contain any bodies, but was an excellent example of the construction and style of burial chamber. We walked down an ancient staircase that was the original entry point, though it was now shored up with rails and covered to prevent sand from filling it back in. As we got down to the bottom and stepped into the blackness of the first chamber it was an odd sensation. I tried to take a photograph and in the end got several surreal photos of ancient dust in the air, which made me think it might not be so good to be wandering down there. I thought back to the stories about the curse of Tutankhamen and the archaeologists who all died mysteriously after opening the tomb. It was speculated that there was some kind of disease or bacteria that was released when they unsealed it. The ancient dust that was so thick in the air could contain all kind of pathogens. Yet a rush of adrenaline and my own curiosity propelled me further into the dark tomb to the slab where the sarcophagus would have been placed. A single ray of light came in from the doorway, showing us the way back out.

It had been an eerie experience to actually go down into the current excavation site where it was not yet prepared for tourists. I felt a little “Indiana Jones” for sure. When we got back out there was a group of men visiting the site and one of them asked Sami some questions, not knowing at first that he was the archaeologist who had worked on uncovering theses sites. It turned out the men were important dignitaries, including a professor from the university and an army commander. They were in civilian clothes, the white robes and hats so common here, and on first appearances could easily have been mistaken for local residents. Sami gave them an interpretive visit of part of the site while I made some photos around the area, then we regrouped and went to visit one of the other tombs which had been restored and was open for public visits. There was a small wind-up powered light that we could use to see the details of the paintings inside. As we started to go through, some school age girls asked if they could come, and Sami welcomed them. They did not speak English, but waited patiently while he explained to me the story of the sun god and the path of life following the path of the sun. He then repeated the story in Arabic for the girls, who were giggling at some parts, and who thanked us and left as soon as he was done.

I thought it was really great to see so many local people appreciating the site, and the fact that the young girls were curious and wanted to learn about it was a very positive thing. It said something important about the culture of knowledge in Sudan. It also said a lot about the role of women in this traditional society. The girls felt free to come and ask to participate. That was important. As we left the tomb a family was coming by and they asked if they could visit it too. Sami left it open for them, and then asked a young colleague to lock it up again when the people had left. In the short time that we were there the site had received these very different local visitors who were given the opportunity to learn a bit more from one of the archaeologists who had worked on the excavation and protection of this important cultural heritage. I felt very glad to be here and to see the positive interaction between the local community members and the UNESCO site. The people were able to benefit and appreciate their own cultural heritage. It was not just something for tourists or researchers. And that meant a lot…

ABOUT THE EXPEDITION

JoMarie Fecci, of USnomads, sets off on an independent scouting trip across Egypt and Sudan in preparation for an up-coming Sahara expedition. Driving locally-sourced Toyotas and working with small local teams in each region, she will traverse a winding route that jumps off from key points along the Nile as far south as Khartoum, where the Blue and White Niles meet. During the journey she will visit a series of UNESCO world heritage sites focused on the ancient civilizations that occupied the region and meet with local communities. The primary goal of this mission is to assess terrain, security, driving conditions, logistical concerns and approximate timeframes for future travel.

WHERE WE ARE

The Sudan in Northeast Africa is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west and Libya to the northwest. The country has a total area of 1.861.484 square kilometres (718.722 square miles), making it the third largest in Africa. The terrain is generally flat plains, broken by several mountain ranges. In the west the Deriba Caldera (3,042 m or 9,980 ft), located in the Marrah Mountains, is the highest point in Sudan. In the east are the Red Sea Hills. The name Sudan derives from the Arabic “bilād as-sūdān” or “the lands of the Blacks.” The population of roughly 37 million people is made up of 597 different ethnic or tribal groups speaking over 400 different languages and dialects. Sudanese Arabs are by far the largest ethnic group, estimated to account for 70% of the population. They are almost entirely Muslims. The majority speak Sudanese Arabic, with some different Arabic dialects, while many Arabized and indigenous tribes like the Fur, Zaghawa, Borgo, Masalit and some Baggara ethnic groups, speak Chadian Arabic. The nation’s official languages are Arabic and English. Sudanese history goes back to Antiquity, when the Meroitic-speaking Kingdom of Kush controlled northern and central Sudan and, for nearly a century, Egypt.